To celebrate five years of taking to their bikes to tour Shakespeare, this young company performed its potted version of A Midsummer Night’s Dream at Rotherhithe’s Brunel Museum. The spirit of fun adventure runs alongside the serious idea of environmentally sustainable theatre which has won them awards. And if you think cycling around with all your kit to put on plays is bonkers – I am sure that they would, amiably, agree with you.

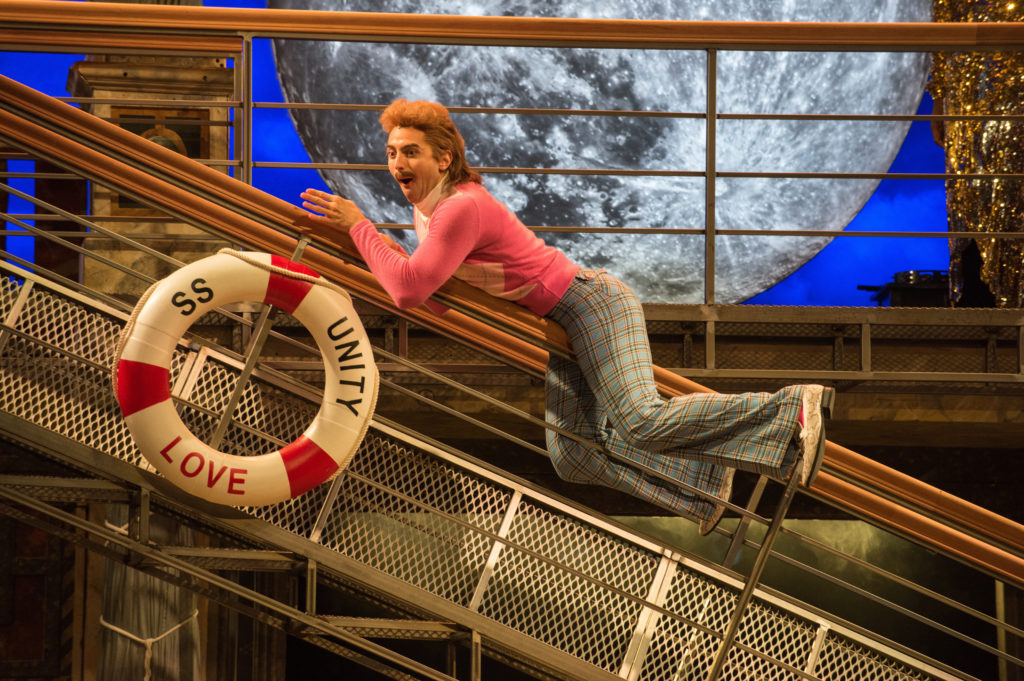

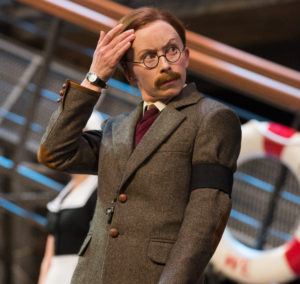

The production is a bit mad, too. Having only four performers is a short cut to laughs. Cycling bells are the cue for characters changing and, you’ve guessed it, audience members are recruited. It’s all out for jolly japes and the company of friends works with a Boys’ Own spirit. Founder members Callum Brodie and Tom Dixon are especially assured, the former stealing the show as both Puck and Hermia. Calum Hughes-McIntosh and Matthew Seager also have experience with the company and it shows – both doing well with improvisation and crowd control. There’s a technical virtuosity that belies the casual feel here, and it’s an understandable flaw if the chaos is too contrived.

There’s no sign that all the cycling has tired anyone out – 12 countries, on three continents, performing to more than 50,000 people over the years – physicality is shown off at any opportunity. There’s now an all-female troupe on the road as well (I’d love to see how they might change The Chap atmosphere), and As You Like It is touring in, ahem, tandem. Comedy to the fore, and all that open air, is clearly working wonders. And good luck to them.

The HandleBards current tour runs through to September 2017

Photo by Danford Showan