Sophie Swithinbank’s 2022 play, Bacon, was one of the finest pieces of writing I’ve enjoyed in a long time. So expectations for this new work, co-created with its solo performer, Phoebe Ladenburg, are high. The writing is complex, arguably too dense for some tastes, but its poetry is stunning. And there’s a strength to the storytelling that impresses. This script really grips.

The scenario seems simple. A traumatic event has led us to a meeting between a mother in prison and the daughter she neglected. The moments when Ladenburg talks to the child are, predictably, moving. But there’s much more from both writer and performer, enhanced by their joint direction. First up is an aggressive awareness that this story is the stuff of true crime drama…and we, the audience, should examine our sense of schadenfreude.

soften, listen

More scenes and characters are introduced: police and prison guards, friends and colleagues of the mother and, as she was an actress, there’s an audition. What the carefully interwoven scenes have in common is how they all judge this woman. Her own request that we “soften, listen” to the story is also a challenge.

Apart from a voice over for her mother-in-law, this is all a one-way conversation, an incredibly difficult task for a performer that Ladenburg makes look easy. And she is careful to leave plenty of room for us to suspect the character, to distrust a lot of what she says.

endless debts

This woman knows she is charming, and Ladenburg has a firm grip on some lighter comic moments. But while the seriousness of events is never questioned, what really went on is. Did her audition actually happen? Is this just an imaginary meeting between mother and daughter? The suggestion is that her sleep deprivation reached a dangerous degree. From here, big questions arise about the expectations around women and motherhood. The text tightens, the poetry escalates, as the mother tries to acknowledge and somehow free herself from the “endless debts” she owes her daughter.

Swithinbank’s gets the most from her accomplished script through excellent design work from Stacey Nurse and Dominic Brennan, whose lighting and sound sculpt the show. The lights rise for direct addresses to the audience, while there’s a black out when the action becomes confused. Sound echoes around the mother, disorienting or showing her distress. Startlingly, the character is sometimes in control of effects, at other moments they seem to take her by surprise. It is a theatrical thrill to see a team at the top of their game. Surrender is a big win.

Until 13 July 2024 then Summerhall in Edinburgh on 1 to 26 August 2024

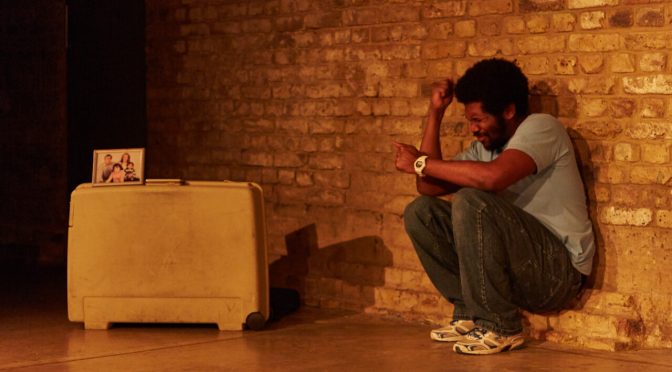

Photo credit Production of Surrender