If you can make a claim for any politician being a hero, it’s Aneurin Bevan, founder of the NHS and the subject of Tim Price’s new play. But there are pitfalls in dramatising this remarkable life. Despite stellar performances and efforts to inject energy into the show, we all know the story and there’s very little to say.

Price does well. We get the story from Bevan’s death bed, so we are ready to shed a tear from the start. There’s a lot of personal history covered, as well as big events to make it feel insightful. A lifelong friend and a formidable wife are brought to the fore, making great roles for Roger Evans and Sharon Small. Oh, and there’s a strong Winston Churchill cameo from Tony Jayawardena. Taking the title role, Michael Sheen plays all ages of the great man’s life while maintaining the show’s conceit – that what we’re watching comes from a morphine-induced stupor. Barely leaving the stage for two and half hours, Sheen delivers a brilliant performance.

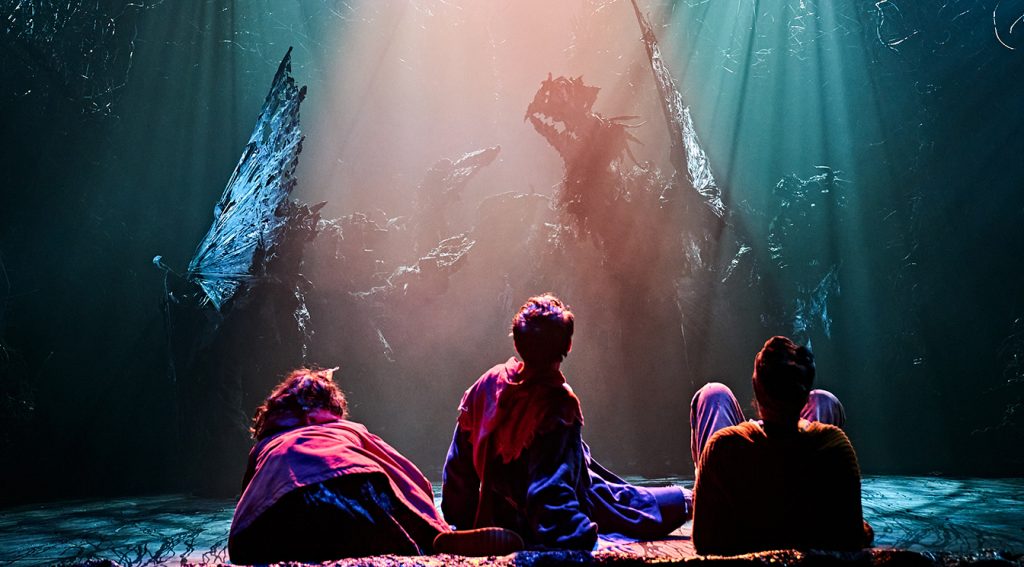

Director Rufus Norris keeps the action rolling with a big bag of tricks. There are lovely moments of movement, with characters lifted and carried around the stage, credited to co-choreographers Steven Hoggett and Jess Williams. A scene in a library from Bevan’s childhood is just gorgeous. Lighting design and projections (Paule Constable and Jon Driscoll) make the most of Vicki Mortimer’s set of giant hospital screens. Clement Atlee’s remote-control desk deserves a mention. And there’s even a song and dance number at one point. You can’t say there’s a lack of ideas. Yet each scene is just a little too long, each idea just a touch laboured. Not only does the show end up feeling like a long night, but all the effort feels clinical.

The biggest problem is that the examination is cursory when it comes to setting up the NHS. Struggles in Parliament and with the British Medical Association, which could make a whole play, are brief. There are goosebumps, but they are down to Sheen, who brings a conviction to the role that is inspiring. Bevan’s outsider status is clear – but it is seen as an advantage as much as a handicap. His growth into power, from activist to politician, is not something to be ashamed of. You can agree with it all, but also note a lack of dramatic tension. There just isn’t much debate in Nye, even if the oratory itself is excellent.

Until 11 May 2024

Photos by Johan Persson