Teen dramas are two a penny. Young lives have plenty of problems, ample angst and content that, as the saying goes, is relatable. A playwright needs to up to the ante with this subject matter. And that’s exactly what Sophie Swithinbank does with her powerful and smart script.

Swithinbank takes us on a journey with her characters Mark and Darren that is carefully plotted. The writing, full of strong yet understated imagery, is admirable. But praise does come with spoilers…

I’ll admit I was fooled at first. The odd friendship with clean-cut new boy Mark and his rough friend Darren has charm and effective (if predictable) humour. There are laughs about the aloofness of one and the ignorant swagger of the other. It seems that Swithinbank will treat their very different problems equally.

In a bold move, the tone of Bacon changes quickly. The teens’ burgeoning relationship, told in flashbacks, reveals not the romance Mark wants but trauma. The play becomes disturbing as the relationship becomes emotionally and physically damaging.

Think of a topic that gets a trigger warning and it’s here: suicidal ideation, self-harm, domestic and sexual abuse. Could some have been avoided and others given more time? But there’s no doubt the cumulative effect is dramatic. Some scenes are difficult to watch as Swithinbank explores how lost and lonely these young men are. It’s depressing how incapable they are of understanding, let alone expressing, feelings.

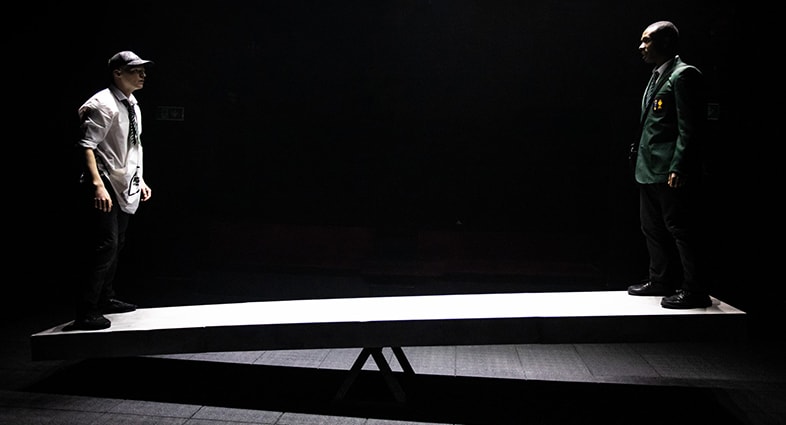

The production rises to the challenge of Swithinbank’s ambition. Matthew Iliffe’s direction is faultless, flipping between relaxed and tense moments. The design by Natalie Johnson consists of a simple see-saw used to great effect: reminding us we are watching children and reflecting instability. Further praise goes to top-notch lighting and sound design (Ryan Joseph Stafford and Mwen) each used dramatically at key moments without being distracting.

As for the performances, two such intense and dynamic roles are gifts to actors. Both Corey Montague-Sholay and William Robinson are flawless, with have a strong command of the comedy (balancing how the audience might laugh at, rather than with, the characters). Montague-Sholay brings out Mark’s charm, Robinson does the same with Darren’s vulnerability, ensuring remarkable sympathy. When violence arrives, we see the characters sharing shock and pain. Strong performances and a daring play make this an easy one to recommend.

Until 26 March 2022

Photos by Ali Wright