For their fifth year of summer residence at St Paul’s Covent Garden, appropriately enough ‘The Actors’ Church’, Iris Theatre presents Julius Caesar. Shakespeare’s political thriller is given a contemporary touch, these Romans are riot police rather than Republicans, but the exciting thing is the collusion of two theatrical treats – outdoor theatre and a promenade performance – that make a winning combination.

Unlike some open-air venues, St Paul’s Church is surprisingly quiet, the acoustics are lovely, so it seems a shame that the acting is often too declamatory. But there are fine performances here: from Matthew Mellalieu, whose Tudor-inspired Caesar is a joy to watch (anyone looking for a Henry ?), Daniel Hanna’s streetwise Casca and Matt Wilman’s virile Mark Antony. Not forgetting Laura Wickham who has a busy night doubling up as two wives and also playing Cinna the Poet – acquitting herself admirably in all three parts.

This is a hard-working show all round. With only seven in the cast there are occasions when members of the audience take on non-speaking parts and all of us are cast as the Roman “rabble”. I am no fan of audience participation but can’t remember seeing it done this well before; director Daniel Winder shows intelligent restraint, creating complicity as we move around to characters’ homes or the steps of the senate.

Taking you through the church’s charming gardens proves ambitious and moving the audience around takes time, this short Shakespeare becomes a long evening, but it’s worth every minute. While the sound design from Filipe Gomes is effective, the actual music accompanying the show is its biggest problem, an inappropriate mismatch of styles, cinematic in inspiration and far too intrusive. It’s a rare bum note in this fine production. The intimacy created is remarkable – at times it’s difficult to work out how big the audience is – and the moments we enter the church itself, with scenes aided by Stephanie Bradbury’s movement direction and Benjamin Polya’s lighting, are coups de theatre you won’t forget in a hurry.

Until 26 July 2013

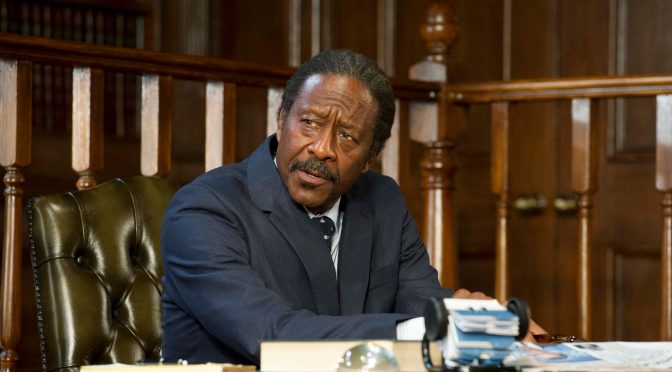

Photo by Phil Miler

Written 2 July 2013 for The London Magazine