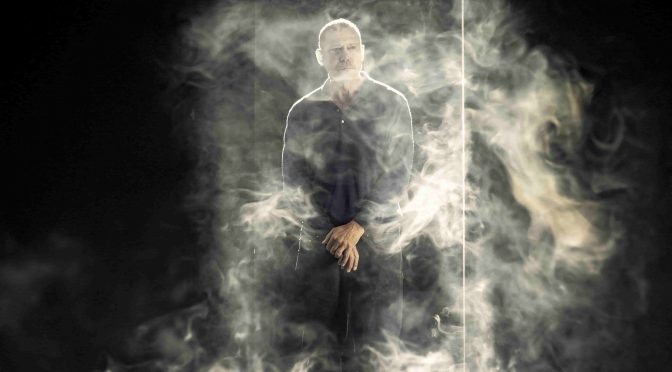

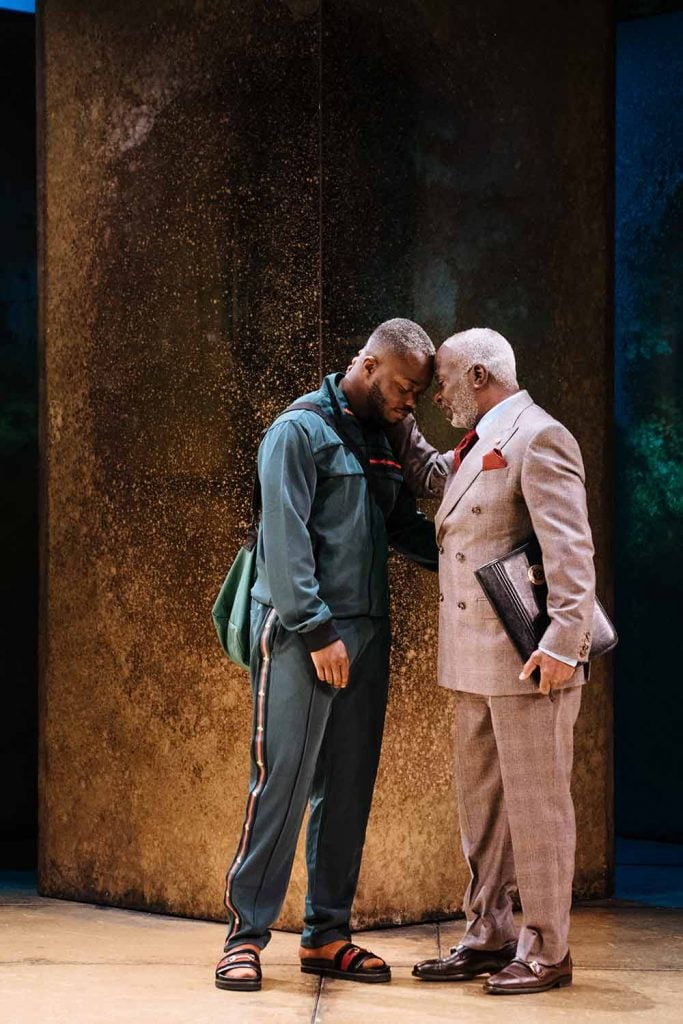

Another fantastic American musical has, finally, reached London. Stew’s 2006 award-winning piece, which follows the adventures of a ‘Youth’, narrated by his older self, is full of big sounds and grand ideas. Ben Stones’ wide-open set makes the Young Vic feel huge. It’s an appropriate stage for tremendous performances from the two leads – Keenan Munn-Francis and Giles Terera – that nobody should miss.

Like Hadestown and Next to Normal (now in the West End), Passing Strange is a very grown-up affair. Despite being a story about a young man, and both leads being magnetic performers, it is the older character we watch. Our narrator is harsh about his early years, coming close to suggesting such self-discovery is just a phase.

There are tough political topics tackled. The ‘passing’ of the title refers to race, but Stew also looks at prejudices associated with being a songwriter – as both he and his characters are. Observations are bravely close to the bone… and specific. The 1970s middle-class Los Angeles milieu is keenly observed (there are sure to be nuances missed). This is the life Youth wants to escape, and we travel with him to vivid depictions of Amsterdam and Berlin.

In each location, supporting performers – David Albury, Nadia Violet Johnson, Renée Lamb and Caleb Roberts – get the chance to shine in a variety of roles. It’s noticeable that the women we meet are treated badly, but the characters played by Johnson and Lamb have great numbers (and tricksy accents). All the time the action is anchored by Youth’s long-suffering mum – a role brilliantly performed by Rachel Adedeji.

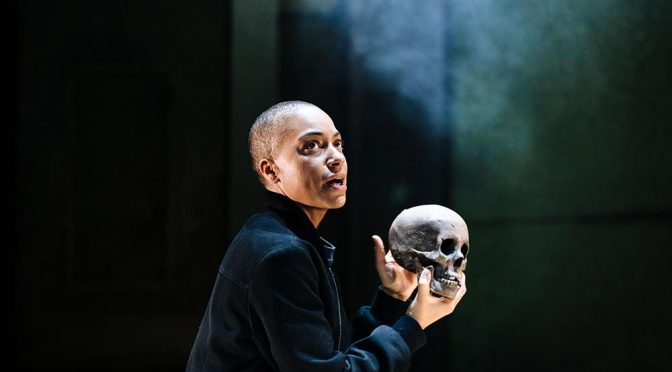

“The head’s footnotes”

There’s also humour in the piece. Again, some depends on understanding what is being satirised. The laughs don’t always fit comfortably in such a serious work, but director Liesl Tommy appreciates the power of such disquieting moments. Mental health is examined as is, as part of this, frequent drug use. As one girlfriend sings, Youth is deep in his “head’s footnotes” (what a great description) and such self-absorption is intense. Like a third recent show from the states, A Strange Loop, there’s an interest in how the mind works that is insightful.

If this weren’t deep enough, the big topic is Art itself. Those questions about the mind, and the past, connect to how we tell stories. Passing Strange looks at how art is made, but also at what it can do, what a comfort it can be. Want another step? The search for “the Real” is an obsessive refrain. Again, it’s about passing – what passes for the real… and what is really real. There’s some profound thinking here, saved from pretentiousness by a big heart and humour.

Given the big ideas, Stew’s songs (the music written with Heidi Rodewald), have a lot to do. The score doesn’t just deliver, it is full of unexpected turns and hugely exciting. While predominantly rock, it serves up a potted musical history with so many styles that it is clear, despite protestations to the contrary, Stew can write anything. Numbers are heart-breaking, funny and dramatic. They are all catchy and their story telling is excellent. The lyrics are consistently intelligent – every word is worth hearing – and matched by superb verse dialogue.

The trials and tribulations of artists can be a turn-off. I don’t doubt how difficult the job is and how much suffering is involved, but they do go on about it don’t they? But Passing Strange plays with such tropes, interrogating them and providing tough love, thereby breathing new life into old questions and sounding great along the way.

Until 6 July 2024

Photos by Marc Brenner