Any show tackling time travel runs the risk of being judged a waste of just that precious commodity. This new musical adaptation by Lauren Gunderson of Audrey Niffenegger’s best-selling novel isn’t that bad. There’s plenty of talent involved – on stage and off. And it is, broadly speaking, entertaining. But it is bland.

This isn’t sci-fi. The story of Henry, who can’t help going back and forth in time, and Clare, who has to put up with his disappearing, is really about loss and grief. Let’s ignore the uncomfortable idea of Henry meeting Clare when she is a young girl and her waiting to grow up for him. Or Henry’s fascination with his opera-singing mother who died when he was a child but who he waits at stage doors for as a grown man. Instead, Niffenegger’s repetition that “love wins” and that it exists outside time is an idea clearly appealing enough for huge success.

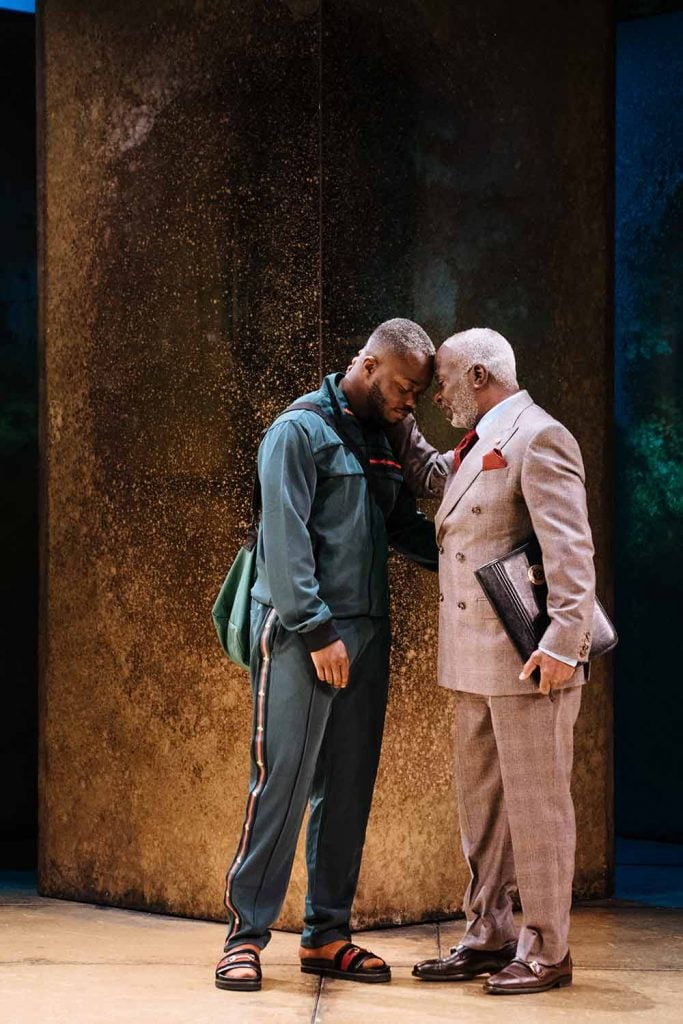

Even if you think there’s always time for romance, I fear disappointment, as the show is horribly rushed. An awful lot of the book has been crammed on to the stage and, as a result, there’s little room for emotion. Too much time is taken working out what’s going on. And this is all despite the efforts of our leads, David Hunter and Joanna Woodward, who sound great, act well, and, alongside director Bill Buckhurst, make sure the action is clear.

The score is a big disappointment. Indeed, coming from Joss Stone and Dave Stewart, the songs are something of a shock. Nothing is unpleasant (although some incidental music sounds like we’re in a lift) but nothing is inspired. And, too often, perky, sweet or swooning sounds contrast awkwardly with what’s going on in the story. And isn’t it downright odd that, despite the time travel, there’s so little variety in the score? There’s no exploration of the time covered by events. The lyrics, credited to Kait Kerrigan as well as Stone and Stewart, are bad. Attempts at humour fail.

Yet there is stuff to praise in the show. Buckhurst has a lot of success with the staging, helped by Chris Fisher’s illusions. Andrzej Goulding’s video and animation work is a highlight. Anna Fleischle’s design, particularly the costumes, are useful. There are also strong roles for Tim Mahendran and Ross Dawes as Henry’s friend and father, respectively. While the main love story is beige, these incidental figures get the best numbers dramatically. It just seems slim pickings for a big show and not worth travelling (far) for.

Until 30 March 2024

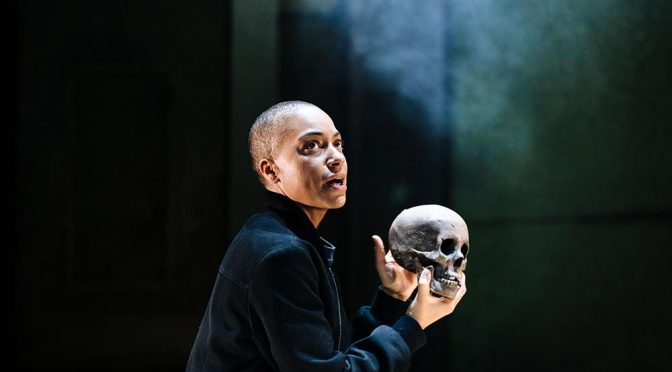

Photos by Johan Persson