It’s surprising that this is the first London revival and West End debut for Martin McDonagh’s 2003 play. Given its author’s fame and the work’s reputation, you might have expected to see the piece more often. It’s worth the wait. The Pillowman is every bit as puzzling and disturbing as I recalled from its National Theatre debut. And if you don’t know the play, then prepare to scratch and shake your head in equal measure.

The reputation isn’t hard to fathom. McDonagh always challenges his audiences intelligently and there’s plenty to think about, while pushing the bounds of good taste makes us laugh a lot. The language is blue (less shocking even since 2003) but, given how much child torture and murder features in The Pillowman, it should still be a hard sell. Even those who like the blackest of humour might blanch at the stories told here.

The teller of said stories is one Katurian, who we meet being interrogated my police in a nameless totalitarian state. The questioning is odd, but just as unsettling are Katurian’s morbid tales, which are quoted to her by the police and told in asides. And that isn’t quite right, is it? All our support should surely be with the writer. But the power of these stories, riffs on fairy tales that even Hans Christian Andersen would think go too far, is the focus. Because someone has been acting them out!

It seems a bit mean to say who the perpetrator is – it’s a good twist. But McDonagh plays with expectations marvellously. Firstly, Katurian’s brother, Michal, who is mentally challenged, loses our sympathy. Then those awful cops start to look… maybe not so bad? They have a story to tell, too. What Katurian gets up to made me gasp. The price this writer is willing to pay for posterity is another shocker.

Such strong material isn’t automatically easy to bring to the stage – McDonagh is demanding of performers. Director Matthew Dunster has engendered fine acting while showing commendable respect for the script. The policemen, Paul Kaye and Steve Pemberton, aren’t strangers to dark humour. If their performances lack surprises, they are still accomplished. Matthew Tennyson makes Michal suitably spooky, and his chemistry with his onstage sister is unnerving. But the star of the night is Lily Allen, who is revelatory in the lead role. Allen shows huge control as her character faces constant violence and horror, indicating how smart Katurian is, yet never going for cheap laughs. Above all, the importance of the work to Katurian is convincing, providing a sense of reality in a play that has so much fantasy and from which nightmares ensue.

Until 2 September 2023

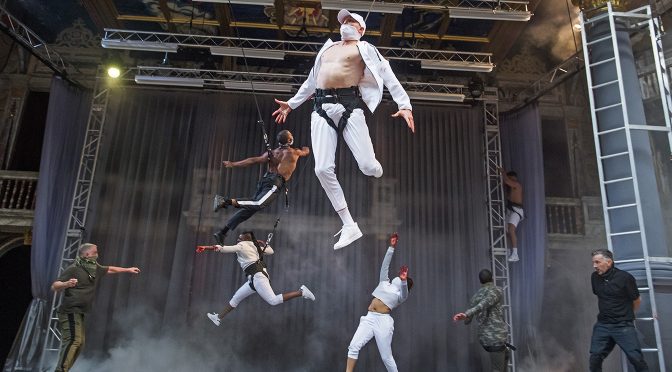

Photo by Johan Persson