John Logan knows a lot about the cinema. As well as plays, he’s written scripts for major movies including Skyfall and Gladiator. His new work for the theatre takes two older films, Marnie and Witchfinder General, and is a tricksy, witty, entertaining piece, with plenty going on.

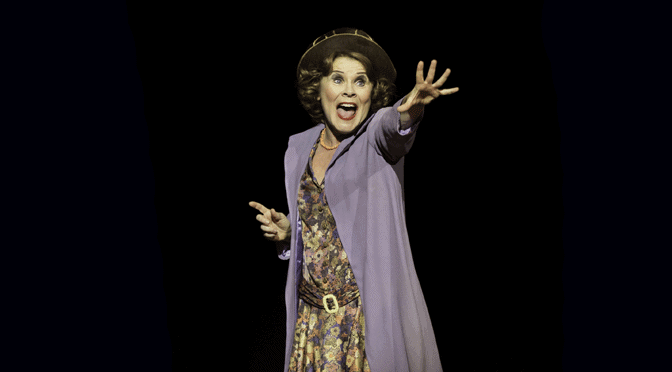

The characters are two pairs of directors and performers from those films: Alfred Hitchcock with Tippi Hedren and Michael Reeves with Vincent Price. So, we’ve got big personalities to enjoy; Logan brings out these artists’ intelligence and gives them great lines. The performances from Ian McNeice, Joanna Vanderham, Rowan Polonski and Jonathan Hyde (in that order) are strong.

Keeping up with who is who and what they do? Well, hold on, despite meeting in different times and places, they are all on stage at the same time. All the action occurs on Anthony Ward’s gorgeous country cottage set. It’s to the credit of the cast and director Jonathan Kent that this isn’t confusing. While the idea elaborates the play’s themes, it doesn’t necessarily make them clearer.

The four are, ostensibly, rehearsing. Although both meetings have darker agendas that provide drama. Going behind the scenes is often interesting; you might consider current hit The Motive and the Cue as a parallel. If you like movies, Double Feature has built-in appeal, there’s a lot of insight here. It’s interesting to see how the directors explain how they work, how they storyboard in their heads. How there’s more than a little snobbery from both Hitchcock and Reeves. And how insecure both actors turn out to be.

The link between each director and their star is clear, the relationships explored in depth leading to powerful moments. In tandem with questions about celebrity (pinning that down is as fickle as fame itself) there’s an exploration of power as well as age and youth – Hitchcock and Price are senior and worried about being “foolish old men”. Everyone reveals a vulnerable side, although Reeves’ poor mental health needs elaborating. It’s Vanderham who steals the show: a horrible #MeToo moment, made viscerally moving, gives way to Hitchcock’s muse turning on him in magnificent style. I felt like bursting into applause.

Maybe, the cleverest part of Double Feature is how much both theatre and film reveal about each other. There’s plenty of talk about honesty and reality, made urgent with Polonski’s cineaste character. He thinks a movie has an advantage here, but this play asks you to think again. There’s a lot of talk about shallowness and substance, with performers simply a face or a big name to be used. But with four on stage, and the text weaving between them, it’s easy for us, if not Hitchcock, to see how collaborative the performing arts have to be. While Kent directs with precision, Hyde’s brilliant Price points out to us how the theatre controls less and demands more. A play becomes a great way to say a lot – the stage does Logan proud.

Until 16 March 2024

Photos by Manuel Harlan