Lucinda Coxon’s new version of Ibsen’s 1896 play gains power from its terseness. Played without an interval, at rapid speed, the story of disgraced banker and his complex family, is an existential exploration conducted in a refined manner.

Borkman’s love of money isn’t quite the kind of capitalism we get nowadays, and Coxon refuses to map some kind of Ponzi scheme onto his actions – bravo. This businessman is a more of mystic. His relationship to the earth, albeit exploiting resources, can’t help but seem odd. Taking the title role, Simon Russell Beale manages to make the character’s conviction believable. And the more we hear from Borkman, the more amazing Russell Beale’s achievement becomes.

Along with astonishing misogyny and arrogance come Borkman’s pleas for his innocence (years after finishing his prison sentence). He lives estranged from his wife, Gunhild, in the same home, which is actually owned by her sister, Ella, who is the women Borkman really loves. And it’s not just a love triangle. Ella turns up to ‘claim’ her nephew, hoping he will reject his parents in favour of her. So much for the traditional family unit.

The bizarre dynamics could leave supporting roles out in the Nordic cold. Strong work from Michael Simkins, Sebastian De Souza and Ony Uhiara (as Borkman’s friend, his son and the latter’s lover) avoid the roles being lost. The psychodrama is fascinating… if extreme. But any melodrama is avoided by a dark sense of humour and Nicholas Hytner’s energetic direction. The sparse staging in monochrome tones in Anna Fleischle’s design contrasts with these colourful personalities.

Two shadows and a dead man

Ella compares herself and her sister to ghosts accompanying the long-deceased Borkman. But her description is wrong – both women are vivid and Borkman full of life. The performances show this admirably. Clare Higgins’s Gunhild is a study of rage, her scorn tremendous. Lia Williams as Ella conveys resignation and desperation in turn, creating a role that’s riveting to watch. Russell Beale is as good as ever as a man utterly deluded yet compelling; Borkman is a caged animal, a wolf, his wife says, containing tremendous power while possessing… none. The bleaker the situation for all three, the more potent the play becomes.

Until 26 November 2022

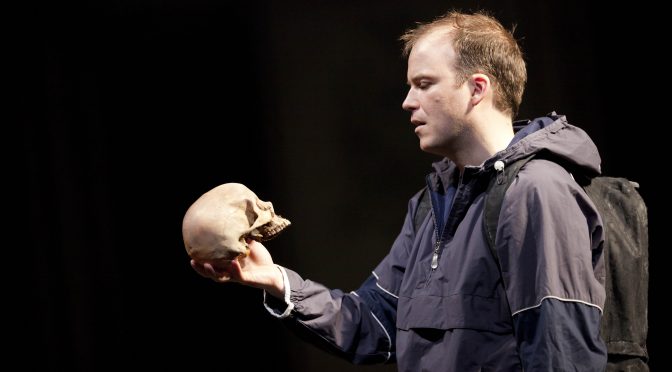

Photos by Manuel Harlan