Simon Godwin’s solid production of Shakespeare’s comedy is perfect for the summer. Setting a play about confusion and miscommunication in a hotel add a farcical, holiday vibe. With live music and an intelligent nod to the play’s self-referentiality, it all adds up to a fine show. The casting of John Heffernan and Katherine Parkinson makes the evening well above average.

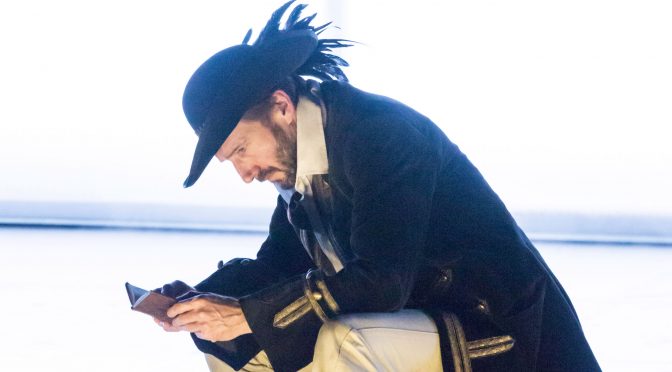

Heffernan and Parkinson are great as the enemies-to-lovers Benedict and Beatrice. From the start, Benedict’s man-about-town act as a confirmed bachelor is only skin deep – which adds to the humour. Heffernan ensures we can tell Benedict is a sweet cynic. As surely everyone’s favourite Shakespearean heroine, Parkinson is suitably spiky but brings an interesting edge to the role. Together their “merry war of words” is fantastic.

It may be ungenerous to point out that the leads’ comic timing is considerably better than the rest of the cast – but it is noticeable. There is firm support for them, especially a good Don Pedro in Ashley Zhangazha, who makes plans for mischief believable. The play’s second love story has a sweet Hero in Ioanna Kimbook and her maid manages ever better – Phoebe Horn makes the most of Margaret’s every moment.

It’s all jolly and it looks great – Anna Fleischle and Evie Gurney’s set and costume designs are a pleasure – but it might be a little slow? A lot of pace is lost with Dogberry, a head of security here, despite David Fynn’s efforts. (And if you want better malapropisms, then head next door for Jack Absolute Flies Again.) The curtain for the interval falls at the moment of the play’s nasty deception, when the marriage of Hero and Claudio is put at risk by the plotting villain Don John. This can be the point where you lose patience with the play (or is that just me?).

Happily, and unusually, the action then takes off. Heffernan is very good at Benedict’s macho moments and Parkinson shows us how deeply Beatrice feels. Kimbook also comes into her own (especially during a scene change).

It’s still not clear why Hero’s lover Claudio, who has treated her so badly, is forgiven (Eben Figueiredo, who takes the role, seems puzzled, too). I guess that’s really Shakespeare’s fault. Godwin deals thoughtfully with the play’s flaws. After the tension, the relief of a party works well. Even Dogberry, recast as a lounge singer, is welcome. The celebration may be brief but as a finale it’s fantastic.

Until 10 September 2022

Photos by Manuel Harlan