Lyndsey Turner’s revival of Caryl Churchill’s classic play has a reverential air. With such variety in the writing – starting with a fantasy dinner party, turning into a domestic drama and becoming increasingly political – there’s no doubting the text’s importance. But in this staging, the humour in the writing stumbles, the edge is blunted and the production is luxurious to a fault.

The novel, and expensive, move is not to double up roles as most productions of the play do. So performers playing guests at the opening scene, women from different cultures and times, don’t reappear in other roles. Using actors the calibre of Amanda Lawrence, Siobhán Redmond and Ashley McGuire for just one scene seems positively wasteful and it also isolates the brilliantly bizarre prologue scene.

There can be no quibbles about the cast – or Turner’s massive investment in them. The play is capably driven by Katherine Kingsley as the highflying executive whose success we scrutinise. And there are strong performances from Liv Hill and Lucy Black as her estranged family. It’s possible these roles don’t have to have be portrayed as quite so downtrodden – Churchill’s point is still made if they are just ‘normal’ people – but the play’s themes of inequality and individuality are depressingly pertinent.

Ian MacNeil’s design is bold in its variety of spaces – restaurant, office and home are all very different – and the scene changes are impressive. And dealing so well with characters speaking over one another gets more praise for Turner. In short, the production is without question technically accomplished. But is all this sleek professionalism necessary? Or appropriate? Does a dinner party with the long dead or fictional characters need so stylish a setting? Or the shabby world of corporate recruitment have to look so lush? Turner has too much respect for Churchill’s work not to present it impeccably, but the play is strong enough for productions to take a more inventive approach with it. There’s a disappointing lack of energy, or anger, that seems inappropriate: Churchill’s message is there, but the challenge is not.

Until 20 July 2019

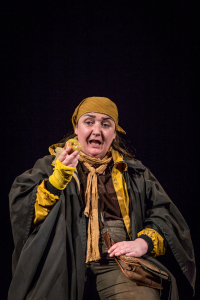

Photo by Johan Persson