This is an excellent revival, directed Lyndsey Turner, of Caryl Churchill’s popular sci-fi two-hander. The scenario of cloned children, head-to-head in conversations with their father, gives instant drama. The sons, played by the same actor, of course, are either discovering their parentage or have been abandoned. How they and their father react means the different scenes offer huge potential for interpretation.

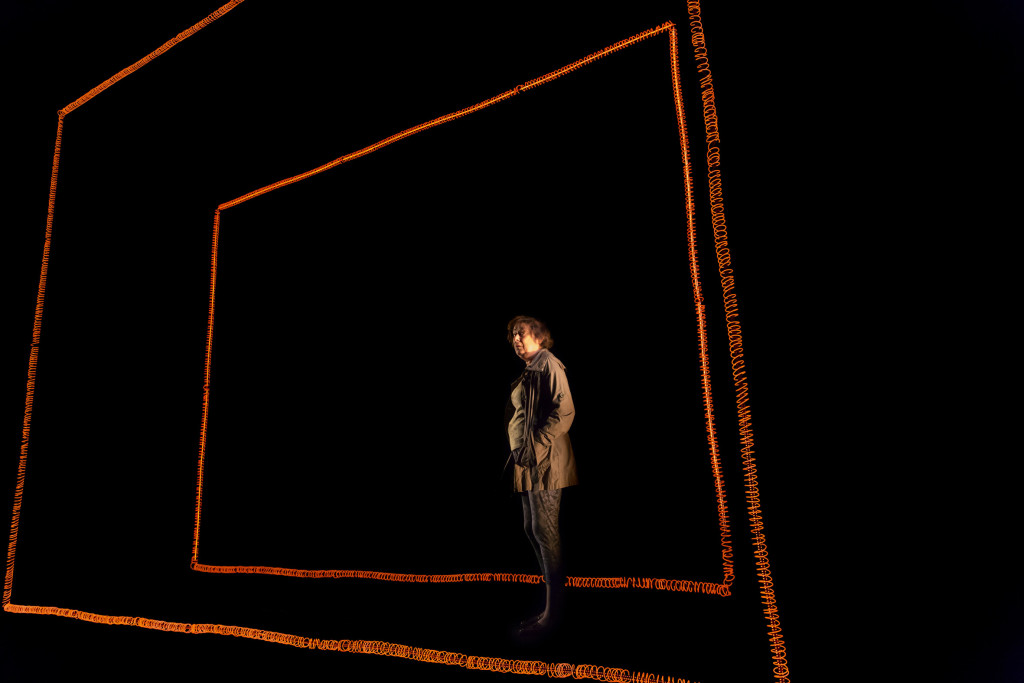

The script is a prospect sure to excite actors, and Paapa Essiedu and Lennie James leap at the opportunities. Which is not to say the play is easy to get your head around. You can see the pitfalls with Es Devlin’s design. Having the walls and ornaments all the same colour is clever – a play on identity and difference. But such concepts quickly become portentous.

“Positive spirit”

Turner avoids the potential weight of the script and the fact that it is a famous play. This version of A Number is clearer, lighter and funnier. Revelations about the father’s history (that could be cryptic or odd) are treated like a thriller: exciting but also creating sympathy. The humour is almost exaggerated, Essiedu especially has great comic skill. The “positive spirit” of the first character we meet (a contrast with another ‘version’) lifts the play. Which is not to say serious concerns aren’t raised.

The nature/nurture debate is explored swiftly and effectively in A Number. Too quickly you might argue, as the show is only an hour long. Essiedu’s confusion, anger or interest in the different characters he takes on are all thought-provoking. Big issues of independence and identity are raised, as are themes of memory and responsibility.

Under Turner’s confident direction, Essiedu and James impress with their ability to bring out the play’s arguments so naturally. These are excellent performances that belie such demanding roles. Churchill’s text is as heavy with concepts as the experiment both men are part of. To make the debate feel so human is a big achievement.

Until 19 March 2022