The star casting of Emma Corrin should, quite rightly, attract an audience to this new play based on Virginia Woolf’s classic novel. Corrin wears their heart on a variety of gorgeous sleeves while addressing deep questions about the identity of the gender-swapping century-traversing character lightly. “Who am I?” interests as much as torments this iconic figure, and Corrin is as energetic as emotional.

For all Corrin’s achievement, it is playwright Neil Bartlett who impresses me most by producing a piece that gives us Woolf’s work… and so much more. Starting with the Elizabethans, Bartlett brings in Shakespeare (from the sonnets to Hamlet to The Merchant of Venice), Woolf, of course, but also a nod to Chekhov, touches of bawdy and even some Kander and Ebb. It’s all tremendously clever and fun. The script is as witty as it is intelligent, as approachable as it is erudite.

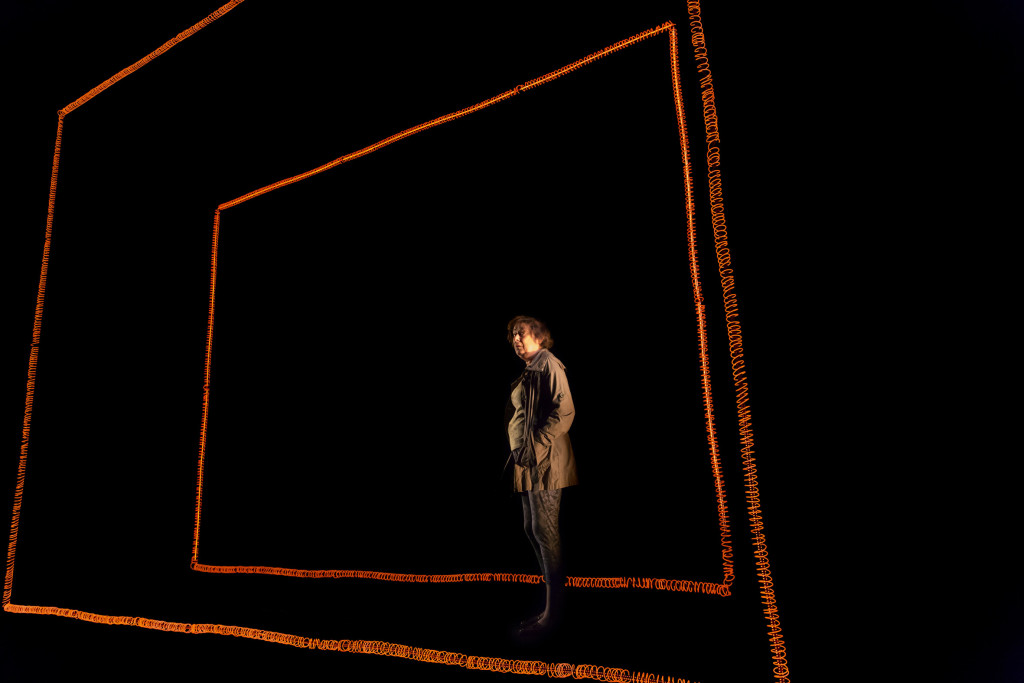

The playful and mind-bending in Woolf’s novel is made to fit on stage marvellously. Michael Grandage’s superb direction takes every chance to enforce theatricality and the result is engaging throughout what feels like a very brief 90 minutes. The pace is startling, yet observations on history and prejudice are clear. The action is guided by the brilliant Deborah Findlay, who plays Orlando’s equally long-lived maid and gets some of the best gags. The sparse staging uses Peter McKintosh’s superb costumes to take us through time and show transformations in simple, effective style.

Bartlett’s Orlando is also about Virginia Woolf. The author isn’t just a character – she is a chorus, with nine performers donning comfy cardis and specs. What would be the collective noun for that? Surely not a pack of Woolfs? The show has too much generosity for that…a Bloomsbury of Woolfs? No, a room of Virginias! The group take us through the writing of the novel, remind us of Woolf’s lectures, while Bartlett’s script shows her as an inspiration. How the work affected Woolf’s life, as well as some of her own story, is interwoven in a moving fashion. And the cast takes on a variety of other roles – different ages and genders again – providing moments in the spotlight for Lucy Briers as Elizabeth I and Millicent Wong as an 18th-century sex worker.

Fluidity is all, and Grandage appreciates that theatre can explore this particularly well. And there’s more. Orlando lives for centuries, but the search for love is always relevant. The show isn’t just contemporary in addressing “Ladies and Gentleman and Everyone”. Constraints imposed by others versus definitions claimed by oneself are examined… and exploded. Background plays a part, with a topical concern for ‘authenticity’ that seems appropriate for a piece so big: Corrin is a star very much of the moment and clearly revels in the radical ideas here. Bartlett presents fluidity on the West End stage with an unapologetic touch that is gleeful. The show becomes an optimistic celebration. Like conditions for women, a recurring theme given its due, things are getting better. All that history has a point, it’s leading somewhere. What is Orlando’s favourite time? It’s now!

Until 26 February 2022

www.michaelgrandagecompany.com

Photos by Marc Brenner