It requires a director as bold as Joe Hill-Gibbins to revel in the oddness of Shakespeare’s ‘problem’ play. Taking licence with the tragi-comic text and its complex moral questioning, this production is radical in the true sense of the word: a far-reaching, thoughtful interpretation that strips it of context and relies on emotional realism.

On the Saturday matinee I attended, Ivanno Jeremiah was unable to perform as Claudio, so first a big thank-you to Raphael Sowole, who stepped up and allowed the show to go on. It’s not ideal conditions but one absence did little to detract from how forthright Hill-Gibbins’ vision is. And, besides, the supernumerary cast of sex dolls more than manages to fill the stage.

That’s right – inflatable sex dolls, which are inevitably what the production will be remembered for. This is a shame since, while irreverent fun, they are not the best thing on offer. With live video recording projected onto the stage, this show gets up close and personal. And, with some help from Hans Memling’s apocalyptic artwork, arresting imagery is everywhere, with a pulsating soundscape from Paul Arditti adding to the atmosphere.

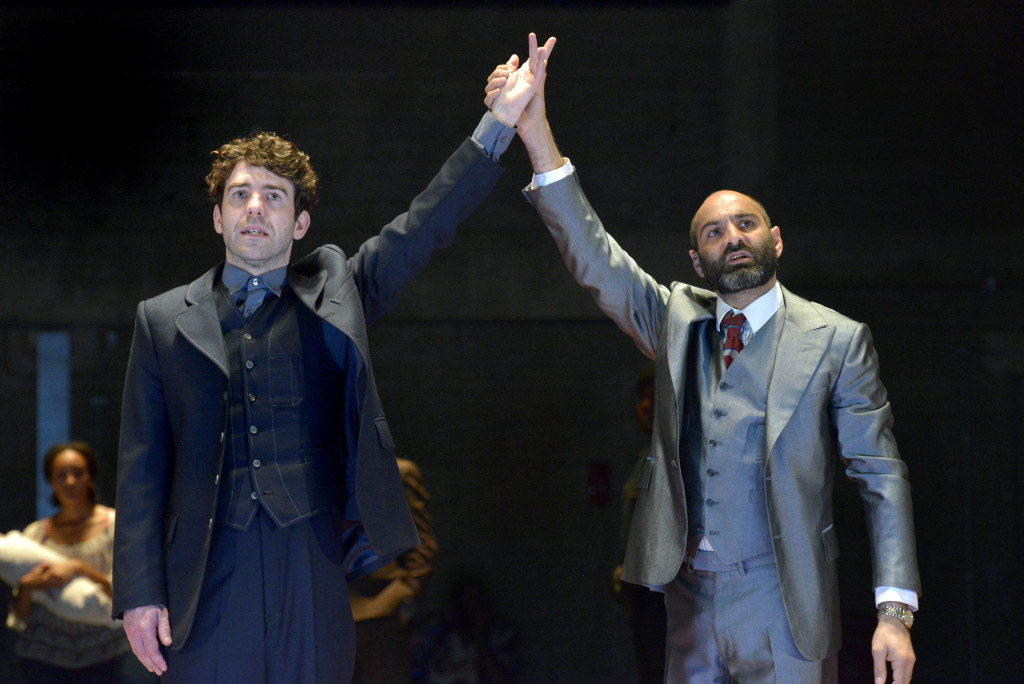

Best of all are the performances. The cast, like the text, is slimmed down and works hard. Romola Garai is brilliant as an indignant Isabella, as is Paul Ready as a cool Angelo – both performers root out the essentials of their characters. There are also strong roles for Cath Whitefield’s Mariana (although why she should be a fan of pop star Pink baffled me) and John Mackay’s Lucio, whose joke with the Duke has far more mileage than usual. It’s with the Duke, given a towering portrayal by Zubin Varla, that Hill-Gibbins should get most credit. This ‘power divine’ is displayed in his twisted benevolent best – a Rasputin gone right, with an injection of tension that suggests his plans could go awry. The conclusion, shuffling the cast into a deranged and confused photo opportunity, makes quite a picture for this flash-bang-wallop of a show.

Until 14 November 2015

Photos by Keith Pattison