Arthur Miller’s 1955 play is far from his best work. Yet this revival, which comes from Bath, has a strong cast, while director Lindsay Posner succeeds in making the text swift and exciting. If the play has dated badly, it still provokes thought, and excellent performances make the most of the characters.

Miller’s setting is specific and vividly evoked – a community of longshoremen who live and work near Brooklyn Bridge. When two “submarines”, illegal immigrants from Italy, arrive at the Carbone home, the already uncomfortable balance between Eddie, his wife Beatrice, and niece, Catherine, results in tragedy.

There are plenty of ‘themes’ in A View from the Bridge. Many feel topical. There’s immigration, of course, where Miller explores how sympathy for those arriving from a poverty-stricken continent comes with conditions. And a contemporary audience will note Eddie’s toxic masculinity and the domestic violence in the play. Posner handles the tension well: Beatrice and Catherine suffer psychologically, and Kate Fleetwood and Nia Towle are terrific in these roles.

Catherine’s affair with newly arrived Rodolfo isn’t written as well – it seems included to reveal Eddie’s inappropriate obsession with the orphan girl he has raised. While Callum Scott Howells brings a strange glamour to the role of Rodolfo (you can imagine a young girl falling for the character he skilfully creates), Towle seems wasted in her part. Similarly, Rodolfo’s brother, capably performed by Pierro Niel-Mee, has little to do. In short, characters are only foils to Eddie.

“Blue in his mind”

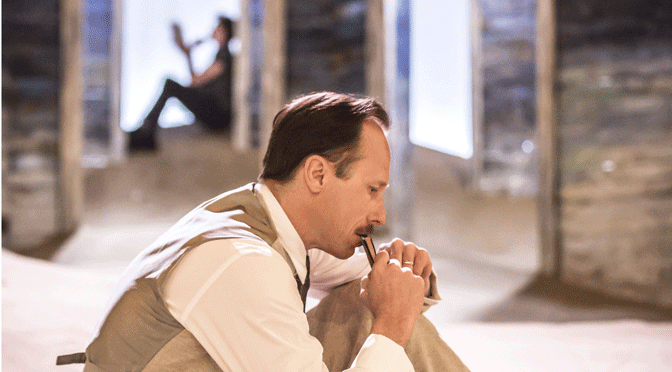

Given the play’s focus, having a star like Dominic West as top billing is essential. West is truly commanding, so imposing that his hold over his family convinces. And he brings an affability to the role that makes Eddie occasionally, appealing. But there is a problem with humour, at least for some audience members, when it comes to Eddie’s homophobia. A conviction that Rodolfo isn’t “right” shouldn’t be something to laugh at. From Eddie’s perspective, it’s a genuine concern, even if he is using it as an excuse to hide his jealousy. There’s no doubting Eddie’s anger (West is excellent here), but, overall, torment is underplayed – it should be bigger than his unrequited lust. Catherine’s observation that Eddie is “blue in his mind” could be made more of.

It’s hard to have sympathy for Eddie. West is good at making him creepy, but the production might have more nuance and offer something fresh if his mental health was given more time. Still, even without it, the play is sometimes slow. A pivotal moment, when Eddie betrays the Italians, illustrates how drawn out it can be. And the role of a lawyer, a kind of narrator, played by expertly by Martin Marquez, is downright cumbersome. All the performances here are strong enough not to need so much pointed out to us. The cast is the reason to see this show.

Until 3 August 2024

Photo by Johan Persson