The frequency of dramatisations and the little learning many of us have about Tudor history make a serious new play about Mary Queen of Scots rather difficult. And Rona Munro’s new play is very serious indeed.

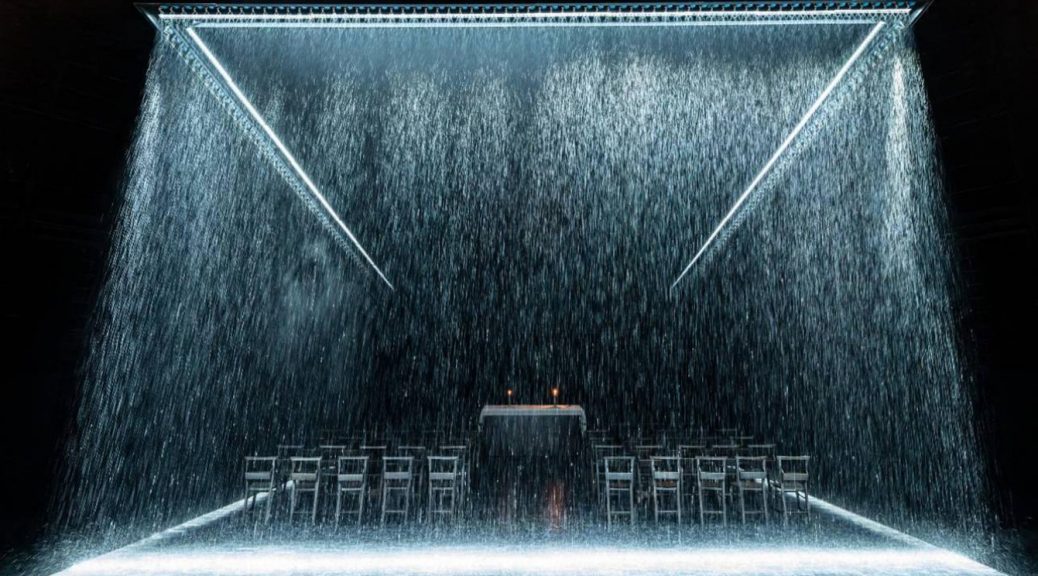

The playwright is an expert. Her James Plays cycle, looking at earlier Scottish history, were a thrilling epic when they visited London. As the latest instalment of an exciting ongoing project, Mary stands alone and shows a master at work. But it is notably starker – as reflected in Ashley Martin-Davis’ design and Roxana Silbert’s restrained direction – and a model of economy.

Munro takes only two moments in Mary’s story – her escape from and then imprisonment by her third husband, the Earl of Bothwell. The thesis is that the Queen was abducted and raped. Munro highlights how impossible it is to know what really went on. The next bold move is that Mary herself doesn’t speak. The play is more about how she is interpreted – and used. And it’s a sorry tale that generates much sympathy and anger.

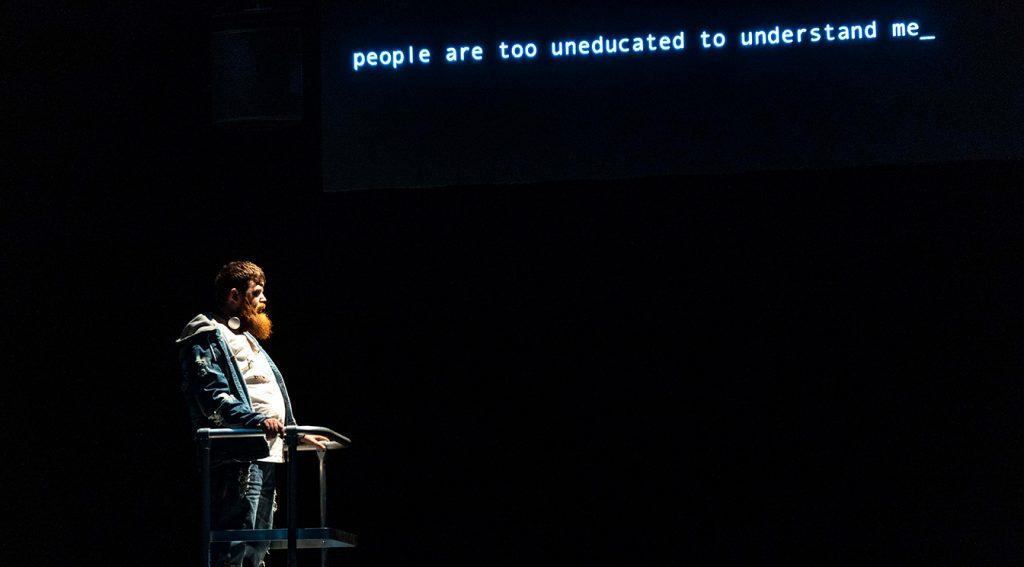

The politician James Melville is the focus. We see him powerful and then broken, with the moral dilemma of how those in power handle cases of sexual abuse full of contemporary resonance. This is a complex role given a strong realisation by Douglas Henshall. Melville is smart, cynical and a stranger to modesty. Seeing his regrets and justifications make great drama. For all that, Henshall’s ability to bring out the play’s dry humour impresses most (and shows a further skill that Munro excels at).

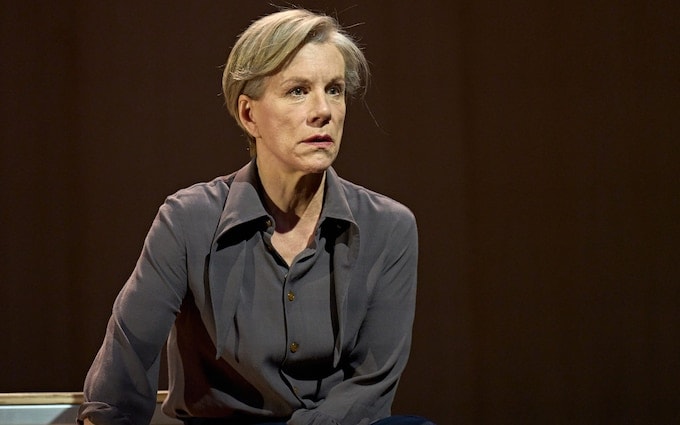

Melville’s interlocutors are fictional characters called Thompson and Agnes. They illustrate realpolitik and religious conviction respectively but still manage to feel three-dimensional. Their passions don’t make the roles easy to perform (Agnes has a damascene moment that might make you pause), but these are strong performances from Rona Morison and Brian Vernel that take into account how a small contact with power can make a big difference.

The three characters talk and talk. It is remarkable how much excitement Silbert maintains in such a static play. The movement comes with minds changing, with characters persuading. Motives surrounding love and power shift and we are left questioning how sensible or selfish each position and character might be. As for the biggest achievement, time will tell… Munro might have managed to change how we think about Mary herself. The play that takes her name is certainly good enough to do so.

Until 26 November 2022

Photos by Manuel Harlan