Rosie Day’s play, which is being adapted for TV and has an accompanying book, is an effective summation of current teenage concerns. The piece is hard-hitting and, appropriately, didactic. Under the direction of Georgie Staight, this limited-run production is impressively slick, and the show is a great vehicle for its star, Charithra Chandran.

We meet Eileen just after her sister, Chloe, has died. Day writes about grief in a sensitive and detailed manner. But the cause of death – anorexia – is given just as much attention. How both affect the whole family and their mental health is explored. And Eileen’s life doesn’t stop because her sibling is dead. She has other problems, including making friends, finding love and earning Scout badges.

It’s a lot, but then so is being a teenager. There are touches of humour, a few impressively dark, but sincerity and authenticity are the order of the day. Thankfully, Day doesn’t make Eileen too mature (an essential key to the play’s success). And the momentum of the show is controlled expertly by Staight. It’s clear from the start that Eileen cares more than she lets on… but it’s still heart-wrenching to realise how tough things are.

With important themes and plenty of drama, the piece is an intense challenge as an 80-minute monologue, but Chandran is superb. She isn’t quite alone. There are also voiceovers and video clips, which prove are the least successful part of the production. Section introductions from Sensible Scout Leader Susan (Maxine Peake, no less) are more than enough to break up the action. And Chandran is heavily miked (although initial feedback was corrected quickly, this is distracting). I’m just not sure any extras are needed. Chandran can hold a stage and tells the story well.

Indeed, for some, the performance will be the most enjoyable part of Instructions for a Teenage Armageddon. To see an actor so in control of material is always a pleasure. For the more jaded, coming-of-age dramas can… lack drama. But the stakes here are high, and Eileen’s encounter with a predatory older man is particularly distressing. Still, there are no surprises, even if it’s all well targeted.

The show’s move to the West End, having started out at Southwark Playhouse, is to be celebrated. It’s great to see a transfer like this, with Day’s and Staight’s skill and hard work rewarded. I’ve no doubt the play will mean a lot to many – it deserves to.

Two performances, every Sunday until 28 April 2024

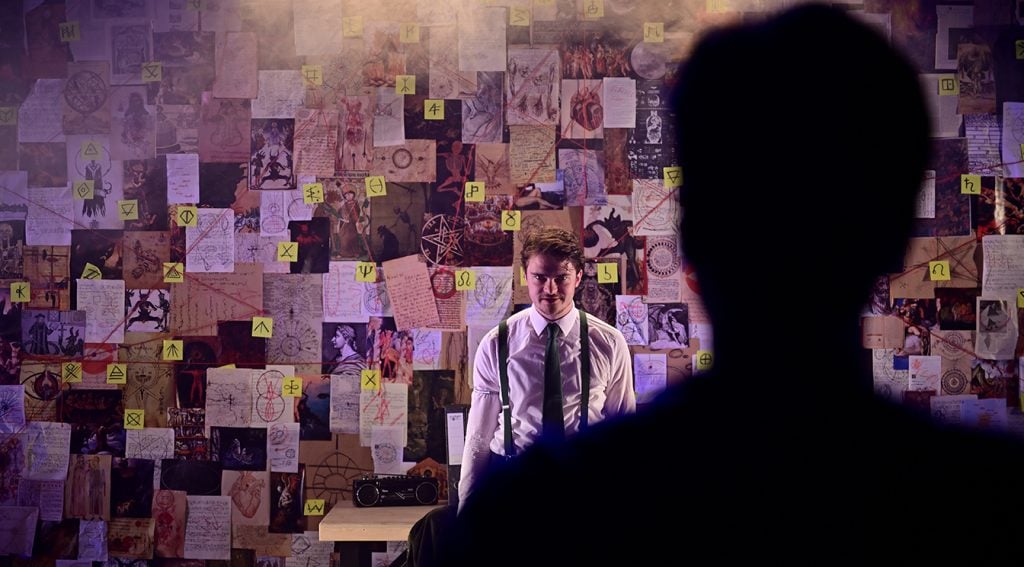

Photo by Danny Kaan