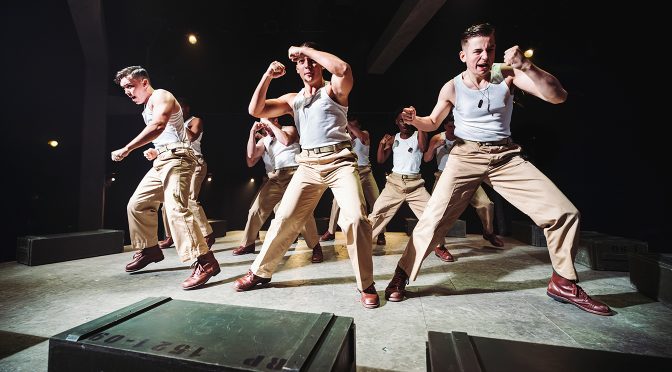

It’s hard not to like this feelgood musical written by Dennis Hackin and based on his film from 1980. Its focus on a “chosen family” and the idea of following your dreams make it tough to knock. The scenario of show people – these ones have a Wild West-themed act – fits happily on stage and the whole evening is entertaining.

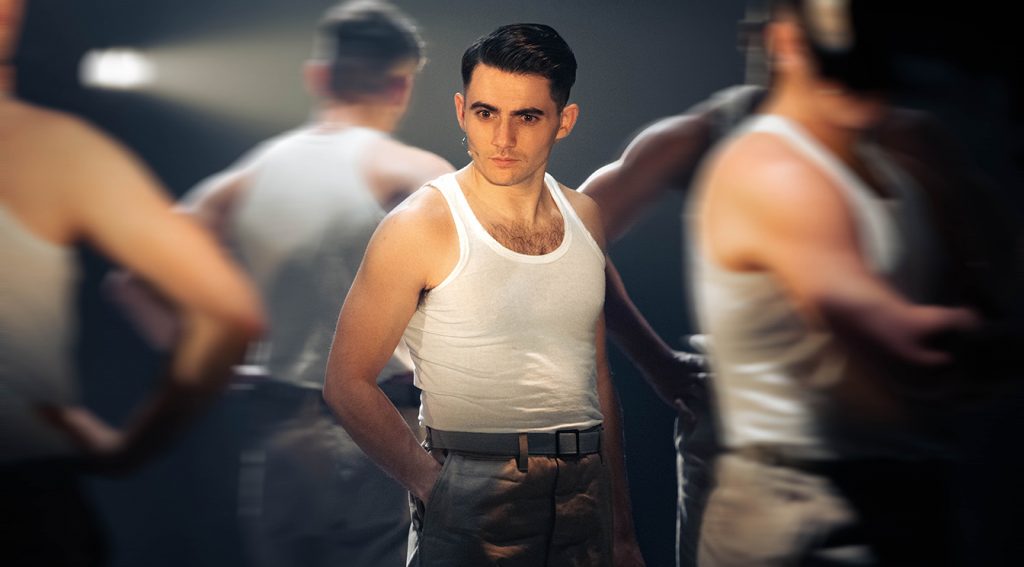

The story follows the titular performer and his troupe, joined by a chocolate heiress, Antoinette Lily, who is on the run. The action is simpler than it sounds and just quirky enough to pique interest. The characters work because they are sweet rather than complex and provide strong leading roles that Tarinn Callender and Emily Benjamin make look easy.

The trick is to have us like the gang. Both stars excel at this. There’s isn’t really much peril for Antionette Lily – she’s smart, has heavily armed friends and there’s a lot of money in confectionary. But Benjamin and Callender make us care about her. They are aided by strong work from Karen Mavundukure as the show’s (slightly wasted) master of ceremonies and Josh Butler as the group’s youngest member. There are no surprises, but it is sweet. Who doesn’t love a misfit with a lasso?

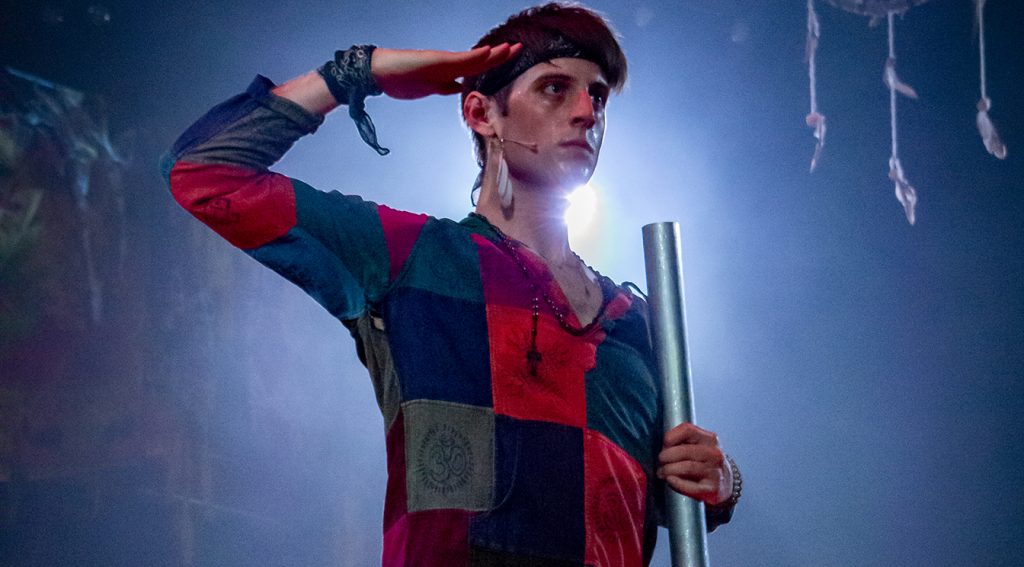

The comedy could be improved (it probably will be during the run). The men out to do Antoinette in don’t have good gags. Slapstick moments are a little too ambitious, the set looks perilous at times, and director Hunter Bird needs to rely less on slo-mo. But Bronco Billy has a secret weapon when it comes to laughs – the show’s wicked stepmother who is out to get that chocolate money! Played by Victoria Hamilton-Barritt, the role has the best number, the best outfits and the best moves and is milked shamelessly.

The music and lyrics, by Chip Rosenbloom and John Torres (additional lyrics by Michele Brourman) all work well. Again, it’s all simple and lacks adventure. The mix of country and western and disco, coming from the 1979 setting, has a potential not fully explored. But every song is effective: well-constructed, purposeful and pleasant. The sentimental numbers are strongest – a couple might have a chance of sticking. It’s all careful and takes care to please.

There’s a lot of love behind Bronco Billy (the show has been in development for a long time). A passion for performing is winning, likewise the theme of family. While silliness is embraced, the central romance ends up believable and the happy ending feels… deserved! If Billy’s cowboy code, full of self-help quotes, is sickly sweet, the show is confident enough not to mind. After all, his inspiration comes, literally, from a chocolate bar.

Until 7 April 2024

Photos by The Other Richard