This quirky musical from the legendary Michael Legrand is a fairy tale for Francophiles. The romance is between Isabelle, an unhappy wife kept under lock and key by her older husband, and a conscientious clerk called Dusoleil. Anna O’Byrne makes a suitably enchanting leading lady, who sounds great, while the show should make a big star of Gary Tushaw, who is excellent throughout. Their intriguing affair is about dreams as much as passion and is transformed when Dusoleil finds himself able to walk through walls!

Being French, Dusoleil turns out to be a superhero with an Existentialist edge – you need a philosophical frame of mind to end up in prison when you could just walk out of one. And he has an eye on revolutionary values, making his alter-ego Passepartout a hero of the people and the fantasy of Isabelle. Turning himself into the law to win his love – he’s too shy to reveal his true identity in any other way – leads to a crazy court scene (including a nun, always a good move in a musical), where Isabella claims her own freedom, leaving her husband and running away with Dusoleil to what should be a happy ever after. Another twist leads to a very odd ending, which ensures the show proves memorable. Suffice to say, Amour is unpredictable.

Even at its climax, and its most fantastical, the show has a strong sense of time and place that adds appeal and plays wittily with caricature. Paris in the 1950s, the city of Legrand’s childhood, is evoked with cigarettes and Camembert. There are some close-to-the knuckle jokes about Nazi collaboration, sexism and the best gendarmes since ‘Allo ‘Allo’s Crabtree. And incredibly, through our hero, communists and Catholics come to agree. Although, of course, everyone is still ready to go on strike.

Amour is charming, escapist and funny. Director Hannah Chissick does well to emphasis all this. She tries a little too hard at times, overusing bikes, suitcases and chairs (the umbrellas are fine, a nice nod to those of Legrand’s Cherbourg). But Chissick’s real strength is to make the show more of an ensemble piece than it might be; giving time for cameos that others might cut. Jack Reitman, stepping into the roles of a doctor, gendarme and judge for the press night, is impressive. And there’s Clare Machin – always good value – as a local prostitute and a colleague of Dusoleil who visits him in prison and steals the scene with an éclair.

Arguably, the biggest achievement comes with the show’s English adapter Jeremy Sams, who dealt with Didier van Cauwelaert’s libretto and took the show, albeit briefly, to Broadway. There are fits and starts, for sure, but the lyrics are funny and often inspired (who knew so much rhymed with Montmartre?). Sams’ work is impressive, but he sometimes seems self-conscious about the poetry. Maybe it’s better to adopt that Gallic shrug on occasion. When letting go, for example, in a number for Dusoleil’s new boss, the results are good (and a boon for Steven Serlin in the role), and when he sneaks in a bad pun it’s a treat.

The real reason to love the show is the score. It’s true that Amour is more a collection of songs than a real musical – but what songs! If there are fussy touches in the production, some flaws in the lyrics, or the story isn’t to your taste, all is excused by a score that is gorgeous, catchy, inventive and adventurous. It shows Legrand, who died earlier this year, in his prime. He wrote music that could makes you smile through its romance as well as its humour. I had a grin on my face for most of the show. Amour stole my heart.

Until 20 July 2019

www.charingcrosstheatre.co.uk

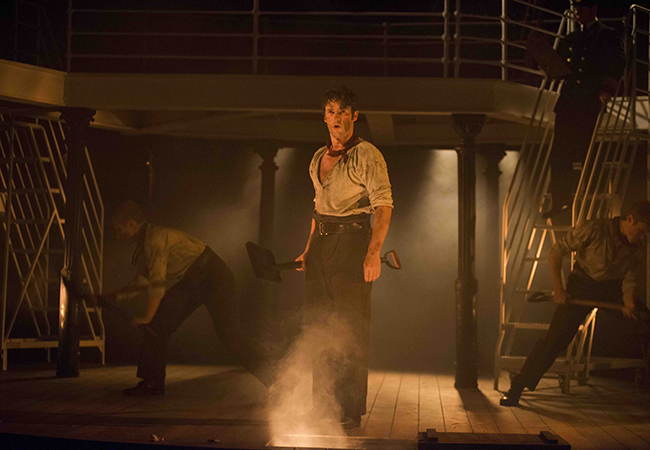

Photos by Scott Rylander