Saturn is the god of the harvest, associated with celebration and also time. In Noah Haidle’s Saturn Returns we meet Gustin Novak at three stages of his life, each focusing on the moment of his greatest happiness – a time he sees as a golden age that he paradoxically lives to regret.

Novak is played by three actors. Richard Evans performs the character in his old age. Irascible and with a wry sense of humour, he is so desperately lonely that he can’t even take advantage of a free airline ticket to anywhere in the world.

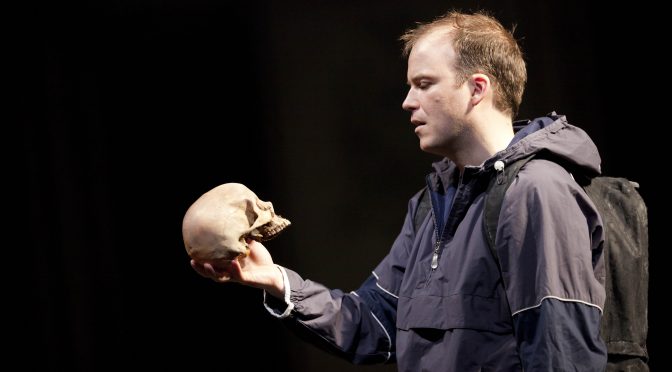

He is joined on stage by his middle-aged self, played by Nicholas Gecks, who brings a frightening intensity to a man bereaved long ago, but still in deep mourning. Christopher Harper plays Novak when young, passionately in love and with his future before him.

All three interact with each other under strong direction from Adam Lenson. They argue amongst themselves and waltz around the stage as they re-enact the past, returning to “the beginning of unforgetting” when tragedy entered Novak’s life. This dance to the music of time is often funny and frequently moving.

This trio achieves a remarkable sense of common identity, but it is Lisa Caruccio Came who just manages to steal the show. She plays Novak’s nurse, his daughter and his wife in different scenes and not only establishes the connections between the characters, but also manages to distinguish them with great historical intelligence.

And this drama has two other stars. Noah Haidle writes with a wonderfully light and poetic touch. This play is bleak but with an underlying tenderness so evocative it borders on the sentimental and is sure to resonate emotionally. A much-lauded writer from the States, it is to the The Finborough’s credit that Haidle receives his UK debut here. Praise must go to artistic director Neil McPherson for once again sharing with us his far-sighted talent spotting.

Until 27 November 2010

Photo by Dan Chippendale

Written 8 November 2010 for The London Magazine