Another adaptation of a Japanese hit has arrived in London, this time based on the eponymous manga series by Naoshi Arakawa. This musical version shares the aim and, arguably, the weakness of a concert production called Death Note from much of the same creative team – the show focuses on fans. Such admirers are numerous, and good luck to them, but other audience members might struggle.

Like a lot of coming-of-age romances, Your Lie in April is unashamedly intense. The book (by Riko Sakaguchi and then Rine B.Groff) is efficient. There’s big drama, with tragedy (I heard a lot of sniffling) and love triangles; all exacerbated by the pressure that these youngsters are training as musicians. Just how repressed the kids feel, might raise eyebrows depending on your age. But there’s a lot for the cast to work with and work hard they unquestionably do.

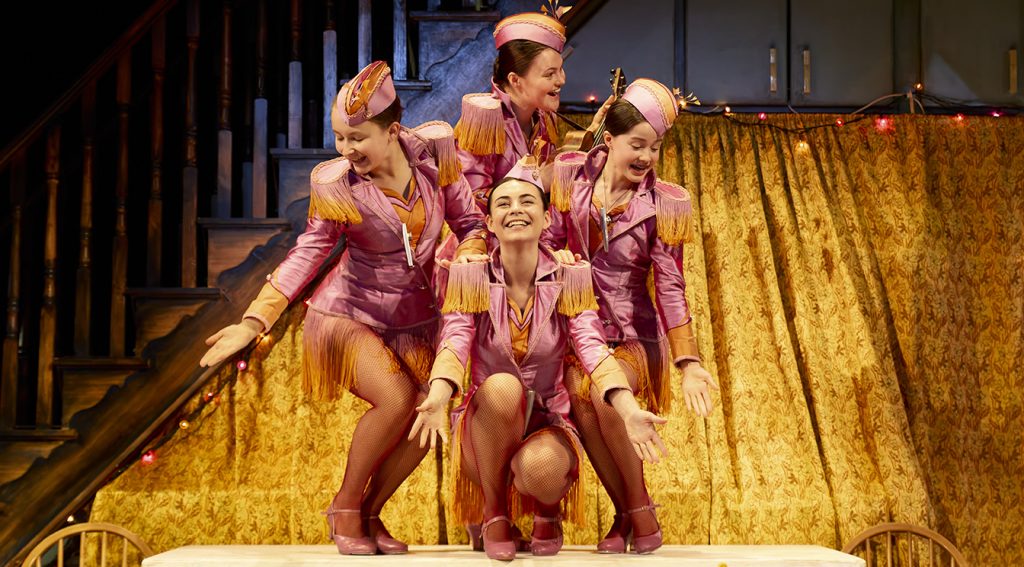

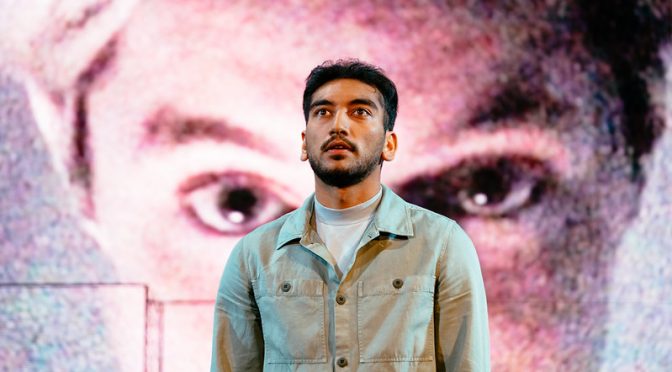

Zheng Xi Yong takes the lead as musical prodigy Kōsei, the “Piano King” grieving for his domineering mother (whose ghost pops up rather too often) and on a journey of self-discovery. Every song is given its all, the performer seemed genuinely overwhelmed by the end of the night. Kaori is the love interest, a rebellious violinist who wants to duet with Kōsei, but who has a sad secret. The character is flat but Mia Kobayashi, who takes the part, makes her feisty and even has a stab at adding humour. Best of all, Kobayashi has a beautiful voice – this is a superb professional debut. If the chemistry between Kōsei and Kaori isn’t great, that’s OK…we’re supposed to find them an odd couple. Their friends are less successful, their stories only foils, and the roles a waste of Rachel Clare Chan and Dean John-Wilson.

There’s a bigger problem though. The lyrics, from Tracy Miller and Carly Robyn Green, are not good: sometimes nonsensical, full of clichés and repetitious. Some of the issue comes from the relentless aim to inspire – it’s all lifting, climbing, flying, while pages are turned and characters “break out”. But nearly every line is predictable, and some are toe-curling: freedom is “really real” and “butterflies can fly”. The words make performances that should be a pleasure feel plodding.

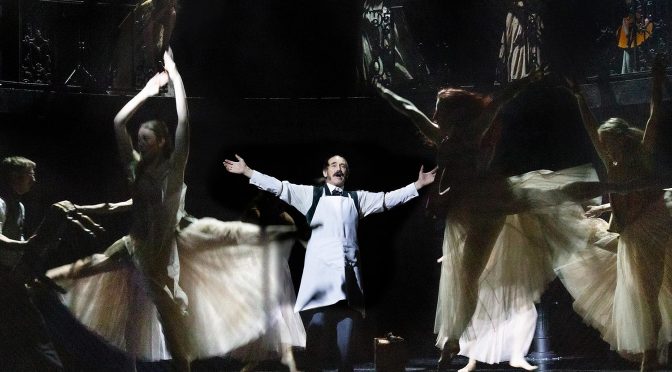

The production is strong. Director Nick Winston keeps the action clear and quick, and makes a lot of effort to focus on emotion. There’s some excellent video design from Dan Light while the lighting, from Rory Beaton, adds a great deal. Musical contests, which structure the plot, make it easy to include the audience – the applause we add is deserved – but such moments are nonetheless highlights. If the classical pieces might be made more of within Frank Wildhorn’s score, the music offered is good; many of the songs are catchy, and a conscientious effort is made to bring in variety.

The music is professional more than inspiring though. There’s an irony here, as the story itself reflects a problem for the show. What Kōsei learns from Koari is that music is about connection rather than perfection. What drives her is the chance to “live in people’s hearts” while a stress on technique has led to disaster – Kōsei literally can’t hear the music anymore. Regardless of how sentimental or neat the idea is, the precision everyone sings long and loud about is ever present. Such polish is an achievement and provides enjoyment. But it lacks a spark, a quirk…something special. Your Lie in April could learn a lot from its own message.

Until 21 September 2024

Photo by Craig Sugden