With characteristic ambition and skill, playwright Jez Butterworth and director Sam Mendes have, surely, created another hit show. Following their work together on The Ferryman in 2017, this new piece can be regarded as a further meditation on storytelling, love and loyalty. It is grown-up, intelligent theatre that lives long in the mind.

The Hills of California is a family drama with four sisters reunited at their mother’s death bed. It’s a big play, as flashbacks show each woman at a younger age – and in the past we also see their mum, Veronica. Mendes and a talented cast make the action clear, the characters are all wonderful studies and the performances consistently good.

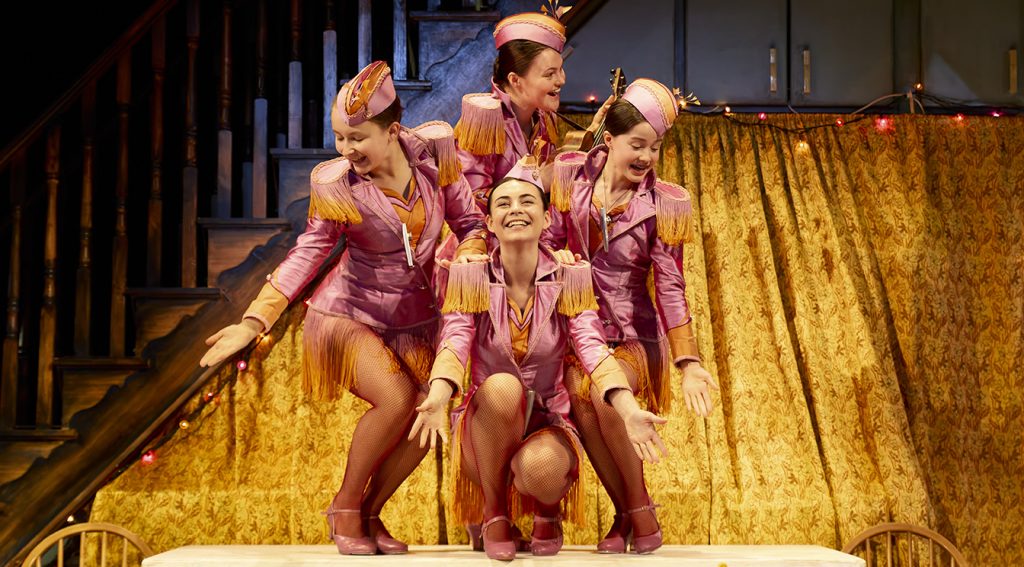

The girls, the Webb Sisters, are drilled as a singing and dancing troupe (think the Beverleys). But only one, Joan, gets a shot at fame in those titular, promised hills. The story behind this chance for success is dark. Butterworth flips effortlessly between ages, showing us dramatic events and their repercussions.

There’s Jill and Ruby, timid in their youth, one staying at home and the other settling for a loveless marriage – roles that Helena Wilson and Ophelia Lovibond reveal with skill. Meanwhile, Gloria is bitter from the start, her anger lifelong, leading to a heart-wrenching performance from Leanne Best. And let’s not ignore other cast members who play the girls when they are young – Nancy Allsop, Sophia Ally, Lara Mcdonnell and Nicola Turner – who we see a lot, sound great and complement the leading roles superbly.

This is a fantastic ensemble, but the show belongs to Laura Donnelly, who plays the mother in earlier scenes and then the prodigal Joan. So, we get to see the formidable stage mother and her main victim portrayed by the same performer. The nuance Donnelly brings to both women is a fitting tribute to Butterworth’s script, complete with uncomfortable suggestions about how cold and cruel both are. There’s a danger of Donnelly taking over – at times the show feels like a showcase for her – but she gives not one but two amazing performances.

The setting – Blackpool in the late 1970s – is vividly evoked and provides a lot of humour. An interest in working-class characters is a key part, for me, of what makes Butterworth’s work stand out. And Butterworth manages better than most to get laughs without coming across as patronising. There are problems with the male roles, which are, surprisingly, close to poor. In the past, a sinister talent scout and a down at heel comedian are flat. In the 1970s, there is a better role for Sean Dooley as Gloria’s husband. But all the men make the play feel baggy.

Maybe it’s that the storytelling the men instigate (be it tales of celebrity or how a juke box works) aren’t that interesting. Or that the men don’t sound as good! Songs tell us a lot here – shared aspirations and then family memories – and they are incorporated superbly and with remarkable confidence by Mendes. Putting so much music in the production is a brilliant move. Mrs Webb describes songs as places – they are a source of promise, providing a hopeful heart to the play, and an optimistic conclusion, despite the past.

Until 15 June 2024

Photos by Mark Douet