A lot of this musical, about a charlady with a dream, is admittedly simplistic. The story is thin – the eponymous heroine works to buy a dress from Christian Dior – while the characters, including clients and haute couturiers, are a bit silly. The music and lyrics, from Richard Taylor and Rachel Wagstaff, share a sentimentality that’s not to all tastes. But it is effective. And since the show isn’t scared of a cliché, let’s add another: Flowers for Mrs Harris is incredibly moving. By the end there isn’t a dry eye in the house.

There are problems with the source material, a novel by Paul Gallico, that Wagstaff’s competent book can’t overcome. This is a patronising view of post-war poverty that is uncomfortable. Observations on class are so blunt they are crass – I’ve seldom heard so many dropped aitches or calls for cups of tea. Ada Harris’ dream doesn’t make much sense, but efforts to explain a gown as a symbol and regard the dress as a work of art lead to some of the best songs and make sure the audience cares about her quest.

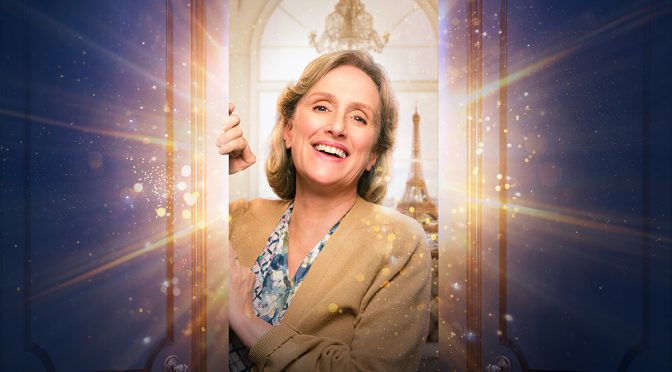

This is a show that aims to be heart-warming and really wants you to care – each character gets the chance to show the best of themselves. It’s easy to praise the fact that our lead is an older woman – a widow with no children – as we don’t see them as a focus often enough. It’s a demanding role that tests even the incredible Jenna Russell’s abilities. Mrs Harris is so unselfish she is hard to believe. That people help her so much doesn’t quite fit with the idea that she is invisible. Nonetheless, Russell manages to give Ada some edge, with flashes of frustration, and makes the character’s charisma clear.

Bronagh Lagan’s direction and Nik Corrall’s clever set make the show feel full, and the standards are high. The production is, however, a little too long. It lacks the zip of Chichester Festival Theatre’s version (although, having seen that online, the comparison isn’t quite fair). Some of the plot twists are good but drag. Take the on-stage presence of Ada’s deceased husband Albert – a role Hal Fowler has a grand go at. Having the two talk and sing packs an emotional punch, but do we need to see Albert so many times to know Ada that is lonely?

It’s the strong contrasts in Flowers For Mrs Harris that make the show winning. While there is a claim that “nothing is out of reach”, final comfort for its character comes with simple flowers. And, while there are many grand gestures, there’s also reticence and modesty. You might claim the such qualities as particularly British – they are certainly appealing and make the musical just that little bit different. The morals are twee, even conservative with a small c, but a show that makes you go ‘ahh’ so often must be doing something right.

Until 25 November 2023