Al Smith’s new play takes us to Bolivia, where tech tycoon Henry Finn and a doctor called Anna bid to mine valuable lithium. Know who your sympathies lie with? It turns out that the former’s electric cars could save the planet, while Anna’s public health project is an ethical nightmare. The dilemma is contrived – most of the plot is just to frame arguments – but the play and Smith’s characters are entertaining.

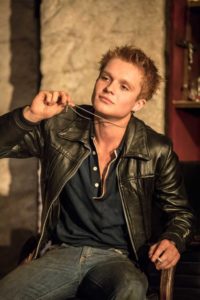

Arthur Darvill plays the parody of Elon Musk. It’s OK – it’s obvious as it’s well done. There’s a base gratification as clichés we expect are ticked off. Smith doesn’t have to be sensitive (could we feel sorry for this neuro-diverse character at some point?) and Darvill is wonderfully overblown. There’s help from a troupe of not-so-yes-men and women (including good performances from Marcello Cruz, Lesley Lemon and Racheal Ofori) just the right side of sycophancy.

Anna the NHS doctor (actually, Strategic Director of the National Institute for Health Research) is even better: a true frosty Brit with gorgeous elocution brought to the stage by Genevieve O’Reilly. With big plans, presented with frightening calm, bribery and blackmail are nothing to her. There’s a fanaticism that is fascinating. In a play that lacks surprises, I was hanging on to O’Reilly’s every word.

Smith is understandably anxious to make sure Bolivians in the play have their say. There’s time in the spotlight for Kimsa, admirably played by Carlo Albán, who lives on the valuable salt flat. And a fictional president, portrayed with conviction as well as cheek by Jaye Griffiths. It turns out both are canny politicians. If crowd-pleasing moments are wish fulfilment, it creates a good atmosphere. And plenty of questions are raised – about history and inequality – that are obviously important.

Issues aren’t scarce in this play. Rare Earth Mettle has an excess of ideas that are far from exhausted. Again, Henry first: his creative notions (credited to his messianic streak) could be challenging if explored more. With the Bolivian characters, there are big questions about the interests of an individual versus their community (local and ultimately global). It’s with our doctor that examining themes of responsibility sit easiest – after all, life and death decisions are literally her job.

The play isn’t short. But nor is it long enough to say a lot, given how much ground it covers. Plot and argument become rushed and too far-fetched. Silly is fine (it’s funny), but predictable is not and too much of the second half can be seen coming at the interval. Hamish Pirie’s direction doesn’t help much – like Moi Tran’s design, it’s inappropriately fussy. I’m not sure what snatches of dancing or a giant pendulum add. But plenty of laughs and strong performances make this an enjoyable play.

Until 18 December 2021

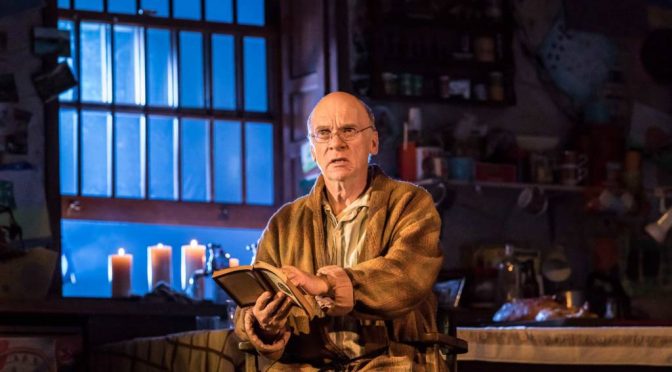

Photos by Helen Murray