Superstar playwright Jez Butterworth’s latest drama was a hit before it even opened: the West End transfer was announced simultaneous to its sell-out opening at the Royal Court and a new cast will soon take the show into 2018. This long harvest day’s journey into tragedy is the story of the Carney family, farmers in Northern Ireland whose connections with the IRA haunt them. This is a big family drama – and not just due to the size of the household, but because of Butterworth’s exquisite writing.

There’s a luxurious feel to the show – although this is a working-class world – created by Rob Howell’s design and director Sam Mendes, who resists the temptation to rush a single moment. Three hours is a long running time for a new play, but every minute holds you. Above all, a huge company, including some extraordinary younger performers, are awe-inspiring. It really shouldn’t be possible to have so many characters so clearly delineated by their own compelling stories.

There’s a lot of laughter in the family, a real sense of warmth, and not a few Irish stereotypes. This has been commented on by Sean O’Hagan, better qualified than myself. To be sure, there’s a lot of whisky drinking and some gags around children swearing seem cheap, if effective. But the stories told, swirling around the discovery of a murdered family member’s body, broaden the play’s themes beyond the Troubles.

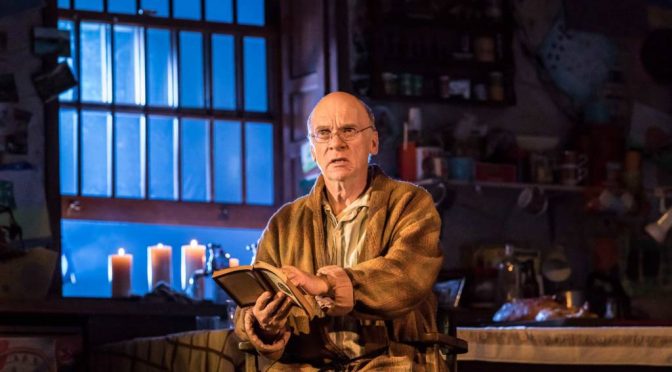

Myth and history populate the play. The past preoccupies Aunt Maggie Far Away, “visiting” from her dementia, and obsesses Aunt Pat, whose brother died in the Easter Rising: two brilliant roles engendering stunning performances from Bríd Brennan and Dearbhla Molloy respectively. Meanwhile Uncle Pat has plenty of anecdotes while, with another strong performance from Des McAleer (pictured top), enforcing the play’s theme of death, which escalates with such foreboding.

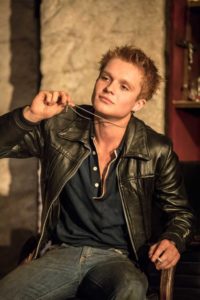

There’s a point to all the marvellously crafted yarns – The Uses of Story Telling, if you’re looking for a dissertation title. The tales form a link to violence inherited by the young. A terrific scene with four youths, led with febrile energy by Tom Glynn-Carney, shows them captivated by accounts of IRA leader Mr Muldoon (Stuart Graham) and the 1981 hunger strikers. In the shadows (there’s plenty of eavesdropping in this play – stories morph into rumour and hearsay, after all) is an even younger “wean”, skilfully depicted by Rob Malone, who is driven to desperate measures.

At the heart of the play is a love triangle that leads to star performances. A repressed affair between the play’s patriarch Quinn, performed with charming assurance by Paddy Considine, and his bereaved sister-in-law Caitlin, a role Laura Donnelly articulates marvellously, leads to some of the best dialogue. Although appearing relatively late, Quinn’s wife Mary is given her due through Genevieve O’Reilly’s quiet performance. The unrequited emotions of all three create an unusual love story that thrums with excitement. As Quinn’s IRA past rears its head with a tension that would please any thriller writer, Mendes’ strengths shine. The fear of what might come next hangs over the final hour of the show. Butterworth manages to juggle all this with enviable dexterity, producing a work of complexity and popular appeal.

Until 6 January 2018

Photos by Johan Persson