Big names make this new musical exciting. Superstar director Ivo van Hove is joined by singer-songwriter Rufus Wainwright and national treasure Sheridan Smith. Not forgetting the name John Cassavetes, the filmmaker whose work the show is based on. Opening Night joins new openings, such as Hadestown and Standing at the Sky’s Edge, in striving for originality: it impresses and intrigues, even if it isn’t entirely successful.

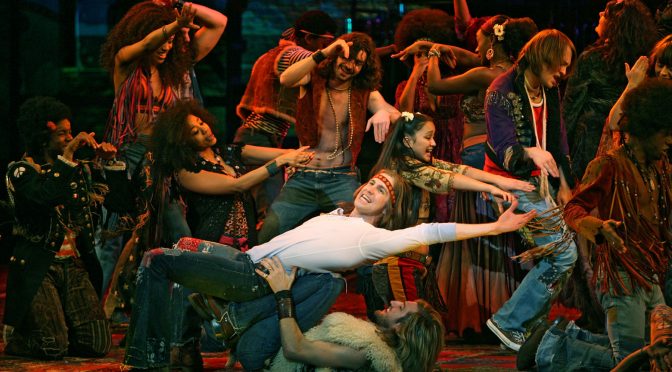

The story is simple enough: a documentary crew is filming the rehearsals of a new Broadway show. That said, interval eavesdropping suggests many in the audience found it hard to follow, because the lines between characters and their roles are blurred. Aging star Myrtle (Smith) is being directed and starring next to old flames. And the producer is in love with her. Meanwhile, the play they are rehearsing is about a mature woman who is desperate for love and struggling with her personal life.

Still, a show within a show is an old trope, even if it isn’t normally played out like this. There’s an awful lot about the nature of reality – Van Hove is far from subtle. So, I guess it’s not so much the story as the way it’s told. There’s a lot of live recording (as usual, Jan Versweyveld’s work is clever), but it’s a shame the recent production of Sunset Boulevard is so fresh in people’s minds. And a red curtain obscures the action a lot of the time. To be generous, it’s surely supposed to be frustrating. There is a conflict between screen and stage that reflects the source material. It is a matter of taste as to how interesting you think this is… it might sound academic.

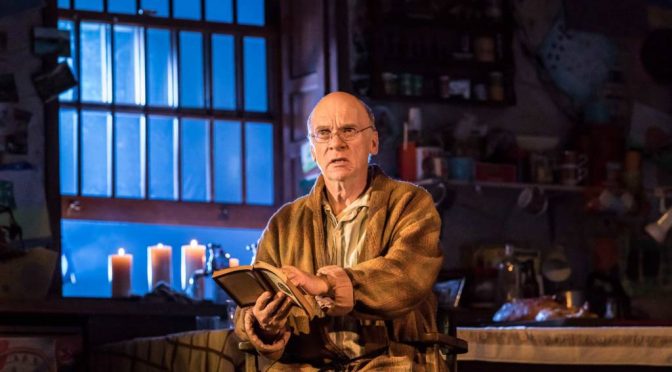

It’s down to Smith to provide emotion and that she does. This is a raw performance, sometimes difficult to watch. Myrtle is an alcoholic and has a breakdown during the show, which includes violent hallucinations about a young fan she sees die. This ghostly role, taken by Shira Haas, is paired with the play within a play’s author, an older woman, performed by Nicola Hughes. Van Hove pivots the story on the theme of “the ages of woman” – not a bad idea, but one that becomes clear too late in the action.

The songs are good, especially those for women. Smith sounds terrific, as does Hughes, who provides a brilliant finale for act one. But I’m not sure there’s enough music to please the musical theatre crowd. And it’s hard to escape the idea that everything would sound better if Wainwright sang it himself.

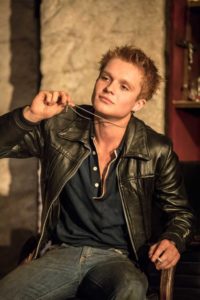

There’s another strong female part for Amy Lennox as the wife of director Manny (she might have the best number as well). But all the fellas are a sorry state. Not that the performances aren’t committed – Hadley Fraser, John Marquez and Benjamin Walker are all great. But all these self-obsessed neurotics are tough to take. Maybe it links to another problem – the play within the play doesn’t seem very good! We can understand why Myrtle is struggling. None of it appears worth the effort.

Struggling artists are, mostly, interesting only to themselves. To be fair, a song from the director reminds them how lucky they are to do the job. So why does the number sound hollow? The show’s surprisingly happy finale – about, of all things, the magic of theatre – also rings false. It’s hard to escape the idea that the show is about irony …and very little else.

Until 27 July 2024

Photos by Jan Versweyveld