Season’s Greetings is the National Theatre’s festive offering to its audience. It has a cast of shiny stars (Mark Gatiss, Katherine Parkinson and Catherine Tate) and might be thought of as well wrapped – designer Rae Smith’s set is impressive. Unfortunately, Alan Ayckbourn’s comedy of Christmas misery isn’t really the kind of gift you want to unwrap.

As a dysfunctional family come together for the festive holiday you can prepare yourself for laughs of recognition. Marianne Elliott’s direction gets the most out of Ayckbourn’s multi-vocal dexterity, but it is a touch laboured. The finale of Scene 3 may be hilarious, but it just takes too long to get there. Ayckbourn’s eye for detail delights some, and this piece has an additional nostalgic charm, but there’s a danger of having too many trimmings – just think about your Christmas dinner.

The cast of nine all get their moments in the spotlight and these are justly deserved but, as each marginally indulgent performance unfolds, the cumulative effect is forced. Nicola Walker is great at crying, Jenna Russell makes a tremendous stage drunk and Oliver Chris is superbly natural as the guest who sets the pulses of the families’ frustrated women racing. It is only Tate’s comic timing that is really spot-on. While Gatiss has great control, his character is so endearing that when the humour gets darker you feel a little guilty about laughing at him.

And the humour does get dark. Ayckbourn plays with the despair of the middle classes in a manner that can’t be described as fun – farce is often close to tragedy and the dark undertones here can take the smile off your face pretty sharpish. You will probably laugh – but it isn’t guaranteed. Nor will it leave you satisfied. It’s a Christmas present you don’t know what to do with afterwards.

Until 13 March 2011

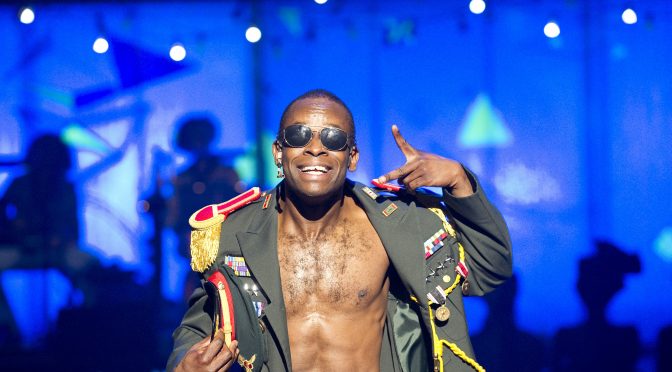

Photo by Catherine Ashmore

Written 13 December 2010 for The London Magazine