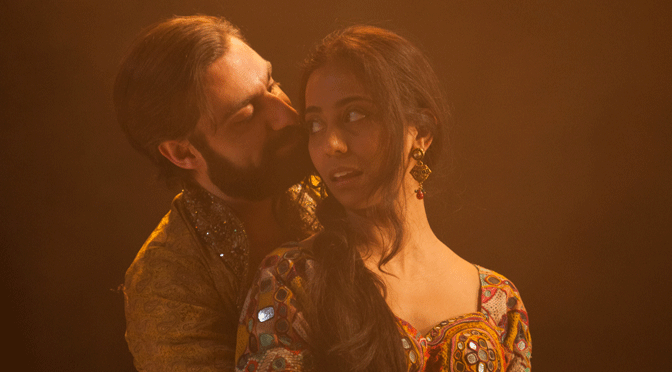

This ambitious new musical, an updated Sleeping Beauty, is a triumph for its designers. The Gothic-cartoonish costumes by Katrina Lindsay are superb. The lighting design by Paul Anderson is sublime. And the staging, from director Rufus Norris, is big and bold. If the show as a whole is underwhelming, it succeeds as a treat for the eyes.

Alas, how Hex looks is the best bit. Jim Fortune’s music is interesting and adventurous, but the show lacks big numbers and all the songs are poorly served by Norris’ lyrics. Tanya Ronder’s book has its moments, but twists on the tale either tire or aren’t explored. The motif of interior and exterior beauty is worthy but feels tacked on. And Ronder seems determined that we shouldn’t like the characters!

A fairy who loses her power is a great idea. But we aren’t given much reason to sympathise with this leading role. Of course, it’s great to see Rosalie Craig, who takes the part, on a stage. But her schizophrenic fairy doesn’t develop and – no matter how forcefully Craig sings – this can’t be disguised.

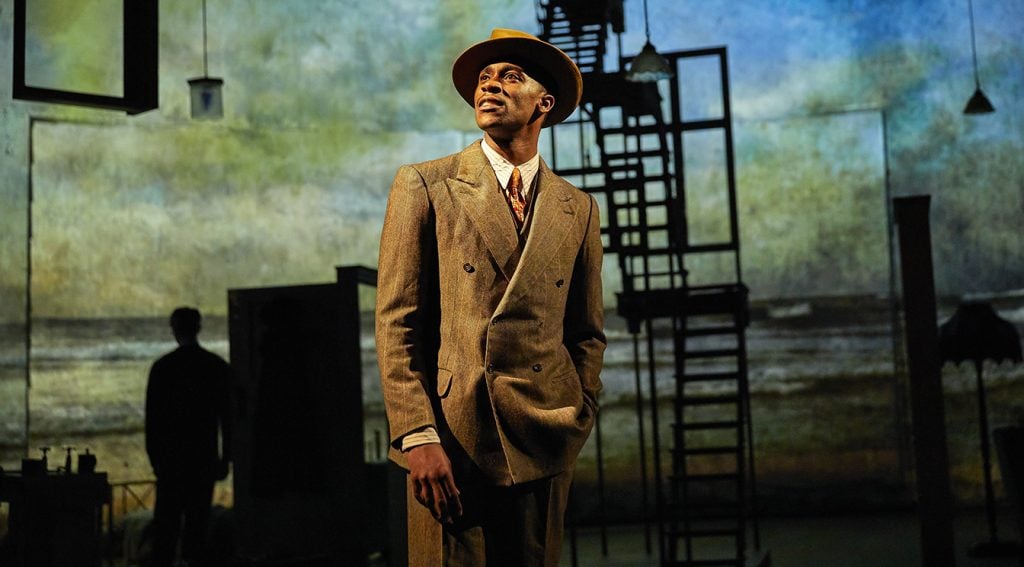

There’s a similar problem with our Sleeping Beauty (Kat Ronney) who is too much the spoiled brat and belts out every note. I had high hopes for her parents (I’d love to hear more from both Daisy Maywood and Shaq Taylor), but these roles desperately need another number.

An ogress as a mother is another idea with potential. And Tamsin Carroll’s performance is tremendous. But a song about coming to terms with eating your grandchildren – a kind of cannibal La Cage aux Folles – is simply a puzzle.

Throughout, there are moments that please. Having the thorns surrounding Sleeping Beauty come to life is great. As is a collection of Princes, who wake up and wonder what to do with their lives – these two groups have the best chorography and bring some fun.

It’s unfortunate for Hex that London has had another new fairy tale, in Andrew Lloyd Webber’s Cinderella, so recently (and that Lloyd Webber got in first). Hex is smart and funny, too – but nothing new. Irreverent twists, strong female characters, and masculinity to laugh at are great, but we can see it all coming. So, the only real magic emerges from the strong design work. And that isn’t magic enough.

Until 22 January 2022

Photo by Brinkoff-Möegenburg