This revival from director Nina Raine firmly establishes Tom Stoppard’s 2006 play as a modern classic. It’s a piece that has it all: history and politics, plenty of philosophy, and a surprising amount of romance. What you find most appealing is up to you, but big themes and complex personalities are juggled well, and the play is hugely rewarding.

Stoppard loves a big timespan, and there’s plenty of history here, from the Prague Spring of 1968 to a Rolling Stones concert at the city’s Strahov Stadium in 1990. The action tracks the politics of Cambridge based Max and his one-time student Jan, who returns to his native Czechoslovakia early in the play.

In other hands an audience could get lost, so Raine deserves praise here: the production is marvellously clear and bravely paced. It is hard not to be overwhelmed towards the end, and the final party scene chat feels rushed. But if it’s ideas you want to hear, you will be happy; Stoppard’s characters can talk about ideology and consciousness, of all kinds, better than most. Politics here is more than a matter of left and right. Instead, the concern is political engagement, to the extent of asking if not caring might be the best way to be a dissident.

It is those who ask questions – the intellectuals – who are most vivid. Max’s die-hard Communism fascinates. Loyal to the party late in life, he is portrayed with skill by Nathaniel Parker. Jan offers a contrast: he wants a quieter life (spoiler – he doesn’t get one), finding his friends’ letters of protest pointless. Yet Jan is made heroic by Jacob Fortune-Lloyd’s sensitive portrayal.

The characters are keen to address a divide between theory and practice. Possibly, Stoppard’s answer, after outlining all that thinking, is focusing on people – through his characters. That’s my preference anyway. And Stoppard knows how important these personal stories are. His creations have rich emotional lives that form another level for the play. Like the soundtrack for the show, or the love poems by Sappho that feature, they interact with, ground if you like, the big ideas.

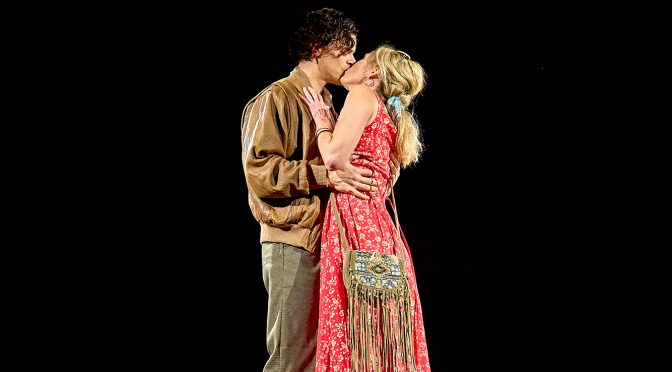

There is a lot of love in Rock ‘n’ Roll, from the mother and daughter relationship that leads to a great role for Phoebe Horn, to the affection between teacher and pupil that Max and Jan show. But it is the romance between Max and his wife, Eleanor, then a young love revisited in middle age for their daughter Esme, with Jan, that provide real warmth. Taking the roles of Elinor and Esme, who love Max and Jan in turn, is a big task but makes an amazing night for Nancy Carroll. These are the roles that provide passion for the play and end up inspiring.

Until 27 January 2024

Photos by Manuel Harlan