There are plenty of laughs while Paul Miller’s triumphant production of Terence Rattigan’s brilliant comedy lights up the stage. This is one of the funniest things I’ve seen in a long time.

The wartime wedding of Earl Harpeden and Lady Elisabeth becomes a farce when she meets two Allied soldiers who make her think again about getting hitched. The trouble is a question of experience: blasé Bobbie has been around, while Elisabeth is too innocent for both their good.

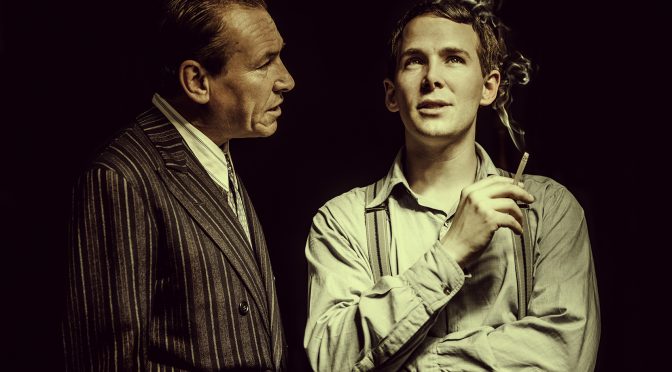

Philip Labey takes the lead as the Earl with an “open boyish manner” balanced by a knowing touch: this toff is nice and not dim. Labey’s is a massive role marked by a generosity to colleagues that benefits all. And Labey has the ability to generate sympathy; for all the flippancy and fun, I wanted the marriage to go ahead. Rebecca Collingwood plays the intended, showing Elisabeth has a mind of her own. Collingwood’s depiction of wide-eyed innocence is funnier than you can imagine – howls of laughter greet the simplest statements.

Conor Glean is an appealing Lieutenant Mulvaney fresh off the boat from the US of A. The performance is neat and the humour gentle. Michael Lumsden and John Hudson play a bluff Major and a refined butler respectively – both to perfection. If Jordan Mifsúd’s Lieutenant Colbert got more laughs from me, put it down to ‘appy memories of ‘Allo ‘Allo. Mifsúd’s faux-French is a skilled work of genius.

Really stealing the show is the man-eater and self-confessed trollop Mabel Crum. I wonder if she was Rattigan’s favourite part? Mabel gets laughs even when she’s not on stage. Sophie Khan Levy’s embodiment of this confident and caring character shows how essential the role is in this carefully constructed play.

It’s Mabel who ends up in charge. Don’t be fooled that she’s continually sent to the kitchen. Prodding male egos in While The Sun Shines shows a subversive touch that has aged well. The distasteful attempts at seduction would have been as off for Rattigan as they are for us, but offence is deflated by how useless the men are! And it isn’t just one couple under the microscope here – it’s the institution of marriage. That Mabel stands aloof from it all makes her a character to cheer. Mabel gets the last laugh. The audience laugh all along.

Until 15 January 2022

Photos by Ali Wright