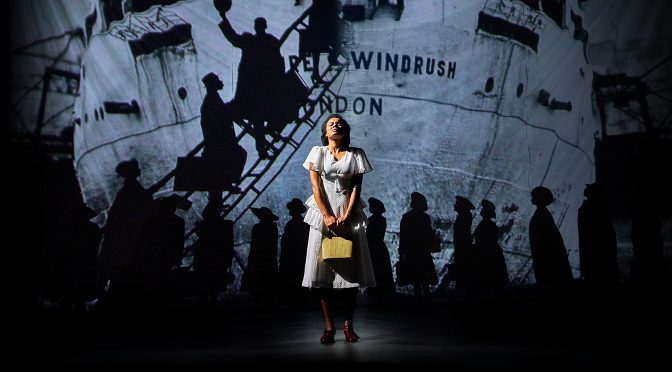

Andrea Levy’s 2004 novel, written long before the national disgrace of the Windrush scandal, feels regrettably pertinent during these times of Black Lives Matter protests. The piece is a painful example of how systemic racism can be – even the most sympathetic character is prone to insulting comments – and it’s depressing to note that the treatment of those coming to our country has never been something we can be proud of.

There’s more to Levy’s work than important lessons about multiculturalism. It’s a long time before the major characters – Hortense and the men in her life, Michael and Gilbert – actually get to the UK. Completing a romantic pentagon, full of coincidence and longing, are Queenie and her husband Bernard. Questions of gender and class are brought the fore with a well-realised sense of a period drama that’s blissfully free of nostalgia.

Such rounded characters are a dream for performers. Leah Harvey takes the lead as the snobby, slightly spiteful, Hortense, who we still come to love. Joining her as Queenie, Aisling Loftus is just as good, and both women bring out the humour in the script that the characters are more the butt of then instigators (bit of shame).

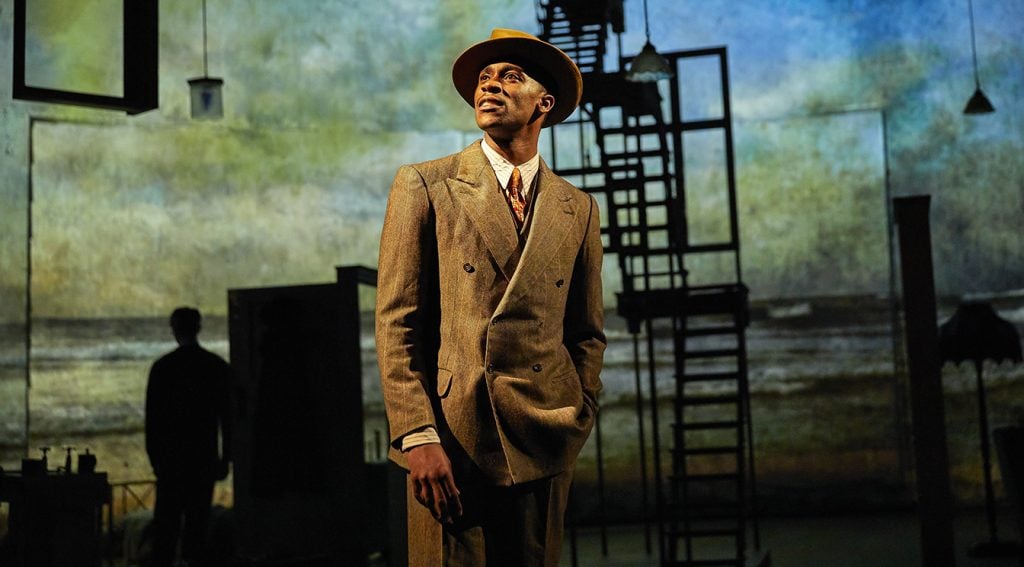

CJ Beckford makes a suitably dashing Michael (praise, too, for Trevor Laird’s performance as his father, who carries the show’s religious undercurrent), while Gershwyn Eustache Jnr’s charm matches that of his character, Gilbert. Andrew Rothney is also excellent at allowing us to see the complexity of his unsympathetic Bernard.

Small Island’s considerable success starts with the fact that it’s a great story. Both Helen Edmundson’s adaptation and the direction from Rufus Norris use the narrative to the fullest to create a gripping show that feels far shorter than its three-hour running time. Katrina Lindsay’s design is impressively minimal, relying on excellent costumes. I’m not even sure Jon Driscoll’s impressive projections are really needed (although the colour in these great production photos is making me think again). The power of the story comes out on the stage, its message hopefully lingering long after viewing.

Available until Wednesday 24 June 2020

To support, visit nationaltheatre.org.uk

Photos by Brinkhoff Moegenburg