If Covid-19 has taught us anything, it’s that the NHS is as emotive and essential a subject for debate as it ever was. This series of monologues, curated by Lolita Chakrabarti, directed by Adrian Lester and funded by the TS Eliot Estate, uses the humanity – and drama – surrounding the greatest of British institutions with a strong sense of purpose. It is essential viewing.

The project started in 2018 but a new commission, from Bernardine Evaristo, starts the line-up online. First, Do No Harm has a personification of the NHS recounting her achievements and challenging us as to her future. Overtly political, with an attack on “myopic puppet” politicians, this effort to give the institution a voice is stirring and powerful. If some of Evaristo’s references, let alone lines such as “I have X-Ray vision”, come close to being overblown, a magisterial performance from Sharon D Clarke makes them work. The effect is tremendous.

Patients

Chronologically, the series starts with Jack Thorne’s charming piece, Boo, performed by Sophie Stone and showing the impact of the new NHS on a young deaf girl. It’s interesting to see suspicion about the service at its inception, and the writing has plentiful details and an admirably light touch.

Another patient’s perspective – similarly fresh and funny – is told in Choice & Control by Matilda Ibini, which has Ruth Madeley’s character getting on with her life in a wheelchair. It may not be “the Rolls-Royce of wheelchairs” but the point about having access to mobility is well made and Madeley has a lovely way with the audience.

Slightly less successful, if a touch more ambitious, Paul Unwin’s piece adds a dystopian twist that makes his At The Point of Need confusing. David Threlfall’s performance recounts how the NHS has touched his character’s life, but in too much of a rush. It is the only piece that ends more depressing than celebratory – a brave effort that backfires.

Practioners

A gentle humour, with an increased sense of awe about the science of medicine, is present in pieces about the 1970s and 1980s. Sister Susan by Moira Buffini and Speedy Gonzales by Chakrabarti show us a nurse and a consultant telling us about their work. Characters to truly admire lead to wonderful performances from Dervla Kirwan and Art Malik.

Pressure on the NHS is carefully conveyed in the piece about the 1990s. Another nurse and another strong role are present in Family Room by Courttia Newland with Jade Anouka. And stress on NHS staff gets a good twist. Newland highlights the difficulty of health workers protesting that fits well with the whole project’s aim.

High points

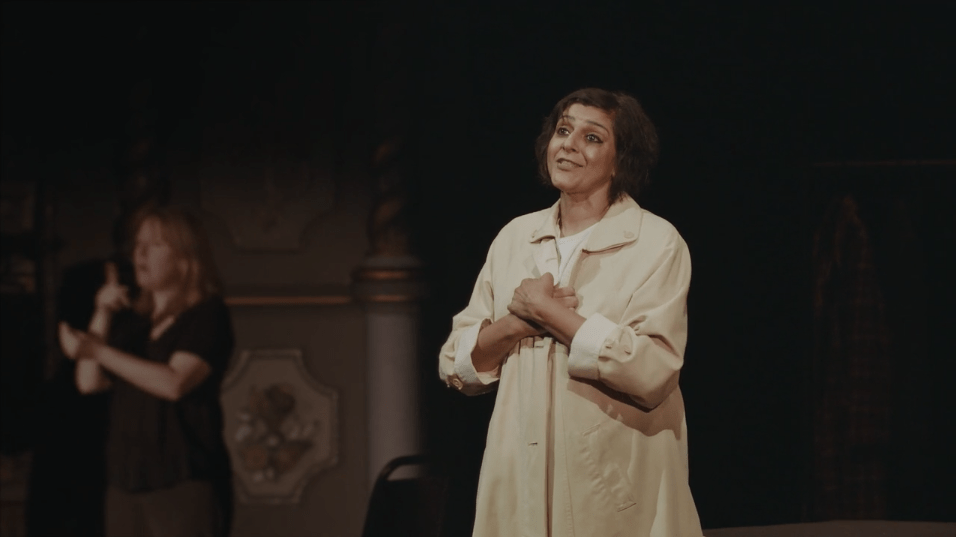

For me, the two highlights of the season contained the most humour, used to great effect in Meera Syal’s Rivers. Performing as a midwife in the 1960s, Syal handles the comedy expertly, with delicious irony and sarcasm. While many of the monologues highlight the role of immigrants within the NHS, Syal has a prime position within the debate and opens it up into a broader look at racism. The result rings true and gets laughs – an impressive combination. With powerful emotional twists, the writing has some great turns of phrase and a lovely rhythm.

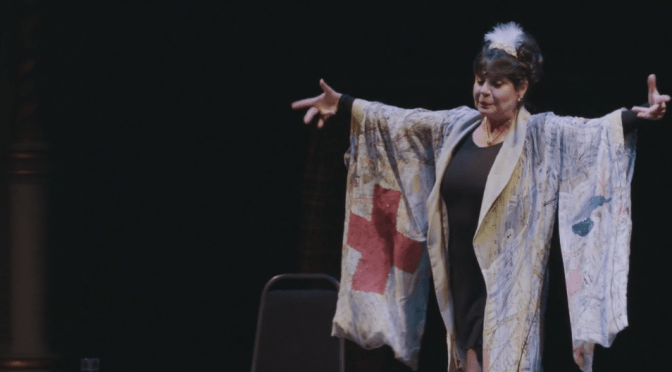

A cabaret monologue, The Nuchess by Seiriol Davies makes for a great change of pace. There’s plenty of satire, including outsourcing the last chorus! And more points for rhyming heaven and Bevan. Performed with exuberance by Louise English (pictured top), this jolly personification of the NHS is markedly different from that in First, Do No Harm. But neither are performances to forget in a long time. The NHS doesn’t lack advocates, but they seldom come as articulate as the contributors here. Let’s hope that a monologue addressing the next decade contains only good news.