Director Antony Page’s new production of Eugene O’Neill’s A Long Day’s Journey Into Night marks a welcome return to the London stage by David Suchet. Taking the glorious role of tyrannical patriarch James Tyrone, successful actor and obsessive miser, Suchet’s performance is spectacular. In charge of a family haunted by the past, and with little hope for the future, Suchet isn’t just technically brilliant – listen as his American accent carefully slips into an Irish brogue – his stage presence is so commanding that it has you on the edge of your seat.

American Laurie Metcalf also returns to London, playing Tyrone’s wife Mary, and her performance is magnificent. Addicted to morphine, administered after the birth of her son, Metcalf’s lucidity wavers as she misguides her family and deals with her own demons. Sometimes painfully honest, at others simply a “ghost” inhabiting her own world, hers is a harrowing rendition.

Mary’s addiction serves to point out the failings of her whole family – the “fake pride and pretence” of her husband and her sons, finely performed by Trevor White and Kyle Soller. As the day becomes drink and drug fuelled, there’s “gloom in the air you could cut with a knife” but in this talented cast’s hands the play manages to remain tense despite its frequently delivered doom-laden conclusions.

To add tension to A Long Day’s Journey Into Night is no small achievement as the play isn’t exactly suspenseful: this long day starts out fraught and doesn’t get any better. O’Neill’s miserabilist masterpiece is a cruel, brutal, examination into family life. Page has cut down the time we spend with the Tyrones – just under three hours – but this is an intense experience that can be hard work. When “the old man” bemoans being typecast you can’t help but think of Suchet and Poirot but, happily, Suchet couldn’t be further from fiction – this is a job he is up to and does achingly well.

Until 18 August 2012

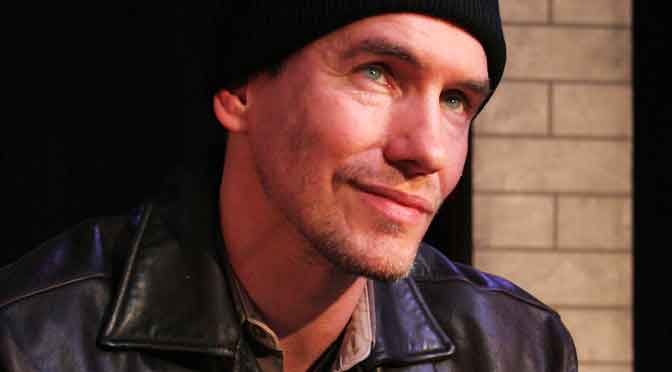

Photo by Johan Persson

Written 13 April 2012 for The London Magazine