The press night for Headlong Theatre’s production of Salome was cleverly planned to coincide with the Solemnity of the Birth of John the Baptist. It served to remind us that Oscar Wilde’s seldom performed play is a religious one. Primarily interesting in that the play shows us a very different side to a writer we all think we know, its director Jamie Lloyd embraces Wilde’s darker side and gives us a sinister, fascinating take on the biblical story.

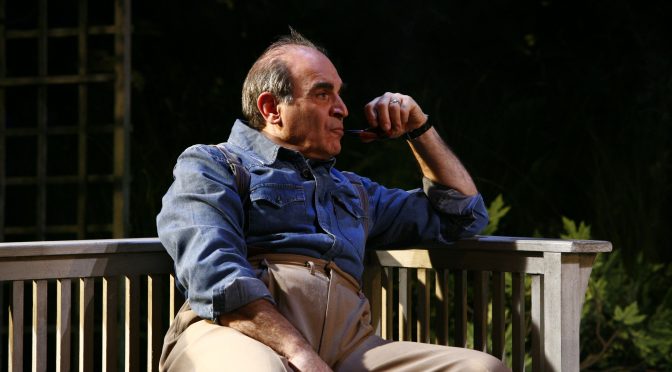

It is uncomfortable viewing. John’s guards are animalistic in the extreme, with movement directed by Ann Yee, they prowl around the stage, quickly establishing an atmosphere of danger and distrust. They have reason to watch their backs. Not just because they fear the wild prophet, played by Seun Shote with an appropriate physicality, but because the court they work at is simply mad. Dripping with decadence, Con O’Neill’s Herod stumbles and spits his way around the stage, revoltingly pouring wine down his throat and over himself. He grabs any and every available piece of flesh – except for Salome.

Zawe Ashton’s Salome is a fascinating creature. Aware of her power, she toys with all the men on stage and revels in the danger. Occasional ineptness reminds us of her age. Jaye Griffiths is in fine form as her maligned mother Herodias. Appearing like a painted doll, her paranoia is at a constant fever pitch. Lloyd has clearly directed all the cast to mark Wilde’s constant warning to “look upon” others. The gaze communicates and increases desire – it has an uncanny power. Not a glance among the ensemble is wasted. The drama is unbearably tense and somewhat exhausting.

Sacrifices have been made to achieve a breakneck pace. Much of Wilde’s poetry seems lost. His text is flushed with colour yet Soutra Gilmour’s set is a dystopian playground and her costumes army fatigues. The symbolism in the play seems neglected – here everything is brutally direct. But Lloyd isn’t running a Sunday School. If events like these really ever happened they probably did so in an environment this crazed, with people this unbalanced. This production casts new light on the Bible story. That was probably Wilde’s aim in the first place.

Until 17 July 2010

Photo by Helen Warner

Written 23 June 2010 for The London Magazine