Nina Raine’s play, a hit transfer from the National Theatre, is exciting new writing. The crafted yet uncontrived piece illustrates how much a talented author can juggle, and Consent is a play full of seemingly contradictory qualities that combine into great theatre.

The plot is a too-simple story of infidelities – a pretty tried and tired topic – as a group of friends, mostly lawyers, make a mess of their marriages. But their motivations, and how their lives change, give the story complexity. It’s essentially a talking heads piece, set around drinks parties and a courtroom drama, but it bristles with an unnerving dynamism.

The theatricality of the law is a blunt point, frequently made, but Raine treats it with finesse. Are the characters’ careers a toxic pollutant of their private lives? Or are the successful barristers closer to their clients than they – or we – would like to think? Raine challenges her – let’s face it – middle-class audience in a sophisticated fashion, laying bare some pretty tawdry emotions with sophistication.

The play couldn’t be more topical. The discussions around consensual sex are only a part of it: the work-life balance of these high flyers is in the news, including their drug abuse, while the obsession with property – and sofas – is tiresomely recognisable. Opposed to this, the battles between the sexes and the classes that Raine highlights makes a claim to be universal: Greek theatre is in the background and makes a fascinating parallel to her work.

Consent is a think piece, cerebral to a fault, with discussions about justice, guilt, repentance and atonement. Yet the play is as emotionally intense as you could wish, with broken hearts all around and characters driven to crazed revenge.

As you might expect with so many abstract ideas, this is serious stuff. But (another contradiction) the play is full of great laughs. Not just dark humour, either – some of the jokes are surprisingly childish and it’s a shock to hear laughs so close to such dark subject matter.

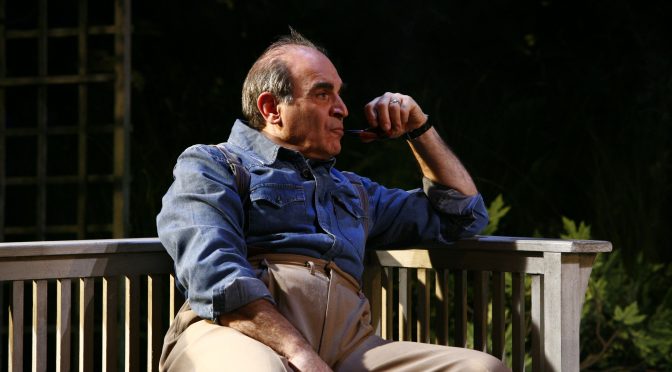

The strong material is meat and drink to the talented cast. Stephen Campbell Moore and and Claudie Blakley are superb as the leading couple Edward and Kitty. There’s strong support from Adam James and Sian Clifford as their friends, while Heather Craney takes two roles with equal assurance. A final accolade goes to director Roger Michell, who tackles Raine’s superb text with such assurance. He’s bold enough to bring out all the tension and subtle enough to show each complexity.

Until 11 August 2018

Photo by Johan Persson