While (seldom) questioning the subject matter a playwright chooses, some should come with a warning. With its main character suffering a degenerative brain condition, Nick Payne’s new play – brilliantly written as it is – makes for a harrowing experience. Elegy calls forth questions as topical as they are uncomfortable and nothing about this play is easy.

New techniques in nanotechnology and neuroscience are knocking at the door, and Payne explores their potential effect on a mind slipping into dementia. They may prove a miracle that extends life, but let’s not use the word cure. Memory is lost and anyone who’s read David Hume will know the consequences of this. Lorna and Carrie, who married each other late in life, find their romance has been surgically removed in the process of ‘saving’ the former. That the person she was is gone, akin to the effects of dementia anyway, is one cruel irony. Another – her inability to recognise her lover means the treatment has worked – makes matters peculiarly grim.

The play is performed backwards. We meet the women after Lorna’s treatment and retrace the steps leading to her surgery. Becoming increasingly involved with this couple, there’s a cruel twist that brought me to tears. The reverse technique, well served by Josie Rourke’s direction, builds tensions and allows three excellent actors to give mind-boggling performances. Zoë Wanamaker’s struggle with the illness is as frank as it is moving. Barbara Flynn is a revelation as her wife: engaging, appealing and torn apart. They are joined by the superb Nina Sosanya as a doctor who slowly reveals her personal motivations behind her professional mask.

It’s Payne’s superior skill with dialogue that’s the jewel here. Painful conversations feel fresh, characters’ attempts at humour and their struggle to comprehend, believable. Particularly in rendering the incoherence of stumbling, confused and truncated speech, the economy and precision of language is brave and haunting.

Science has long been a theme of Payne’s – putting people into the equation is his skill. Elegy ups the stakes and demands a great deal. At its heart is the complex question of what makes us human, encompassing faith, love, history and our responsibilities to each other. The fear that we’re on the brink of unknown territory is palpable. Away from dystopian fantasy, this play feels real enough to give you nightmares, propelling us into the messy heart of a dilemma with piercing skill.

Until 18 June 2016

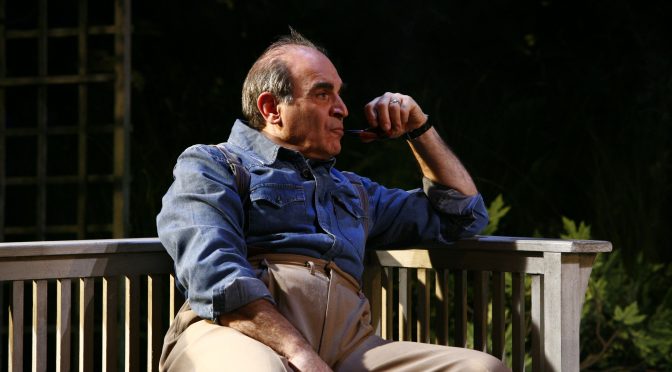

Photo by Johan Persson