Roy Williams’ excellent adaptation of Sam Selvon’s novel about the Windrush Generation is brought to the stage with style by director Ebenezer Bamgboye. A collection of memorable characters and moving stories are depicted with care and passion by a talented cast.

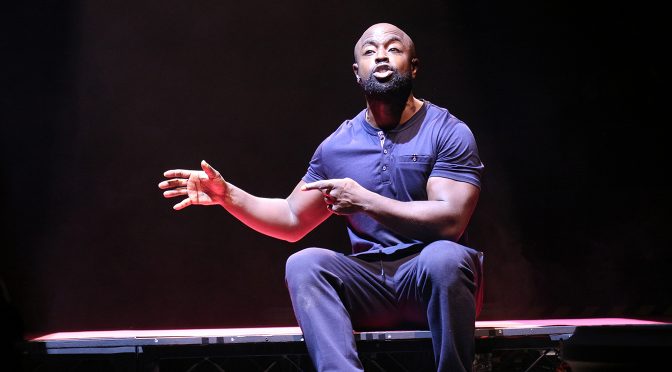

Driving the action is Moses, known as “Mr. London”, who helps out new arrivals to the city. Gamba Cole takes the role with plenty of charisma while his character’s moving backstory is revealed with skill. Moses is joined by Galahad, Big City and Lewis – with strong performances from Romario Simpson, Gilbert Kyem Jnr and Tobi Bakare respectively. Each character is beautifully realised and interesting.

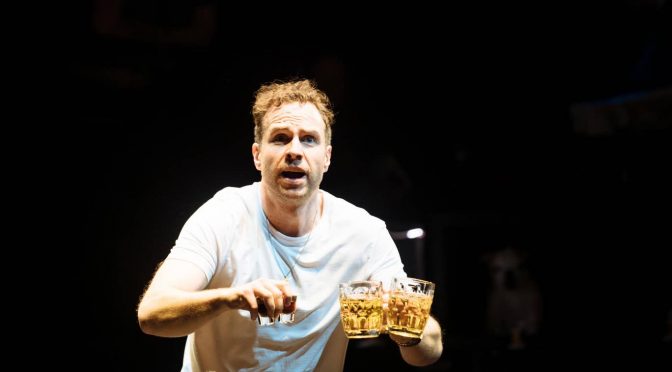

The problems the men encounter are many but Williams makes sure none of them feel underexplored. The racism they face, the isolation and rage it creates, is painful. All four brim with frustration, ready to snap at any moment. But broader ramifications are also clear: depression, poverty, the potential for crime, and toxic masculinity. The men are presented with a collection of objects – gun, dagger, and hip flask – the tension Bamgbye generates around these is fantastic. And there’s no idealizing the men or the story. Moses’ assessment that they are lonely but not alone is consolation but doesn’t generate false hopes.

It’s a shame the women in the piece have poorer roles. Moses is haunted by Christina, the love he left behind. Lewis’ mother and wife arrive in London but start too comedic and then come dangerously close to exemplars of how to adjust to a new life. Thankfully brilliant performances save the roles: Shannon Hayes and Carol Moses have tears in their eyes in their key scene – powerful, impressive acting.

For all Williams’ skill and the importance of the history, it is the staging rather than the stories that make the production stand out. There’s Elliot Griggs’s bold lighting design for a start, a model of effective simplicity that works brilliantly in scenes of violence. Aimee Powell’s gorgeous singing as Christina weaves throughout the show, part lament but also encouragement. Stirring choreography deserves final praise. Extended sequences that use movement, directed by Nevena Stojkov, are mesmerizing. Illustrating affection and aggression in equal measure, showing, by turns, a sense of loss and anger, brings home the complexity of these lives.

Until 6 April 2024