While its back catalogue of broadcasts from NTLive was a blessing during lockdown, being back on the South Bank for a show in real life is the real deal. For those lucky enough to have caught the brief window of performances, before a second closure, this new play by Clint Dyer and Roy Williams was a very special occasion.

An introduction from creative director Rufus Norris, justifiably proud of his theatre getting back into action, added to the atmosphere. The caution shown around protecting customers is clear: there are allocated tables before being taken to seats and – beware – last orders for pre-show drinks is in the afternoon.

What of the play selected to welcome theatre devotees back? As well as the important subject matter of racism, Death of England: Delroy is topical. After seeing shows years old, it’s good to be reminded of how quickly theatre can respond to current concerns.

A sort of sequel to their show last year, Dyer and Williams develop a character mentioned in their previous monologue, Death of England. Recounting a “very bad day” Delroy has had – quite randomly – this likeable character runs into trouble with the police. Serious consequences include estranging him from partner and new-born child.

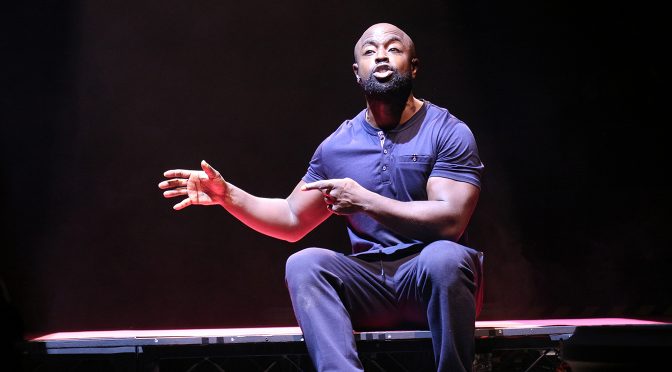

The show provides a starring role for Michael Balogun who is superb. It’s amazing to learn he was drafted into the project last minute. A rapid-fire delivery shows remarkable confidence with the script. And his level of energy over 90 minutes is astounding.

Welcome as the show is, it would be wrong to say it’s perfect. The Olivier is an unforgiving space at the best of times and the Covid-reduced seating feels particularly detrimental. All the more credit to Balogun for creating an atmosphere that ranges from convivial to confrontational.

The unusual conditions can’t be avoided. But Dyer’s direction creates problems too. It’s understandable that all aspects of design (the set by Ultz, lighting by Jackie Shemesh and sound by Pete Malkin) want to show off what the National is capable off. Like us, the team is thrilled to be back in the theatre. But does this show need any extras? Loud, dazzling, effects and some pretty naff props (including an explosion of confetti) are not needed with such a strong script.

Because the text itself really is excellent. The bravura language, which Delroy aptly describes as a “riot in my mouth” is provocative and funny. The ease with which ideas are raised is impressive, including arguments both enlightening and far-fetched (a motivation for voting to leave Europe is worth a raised eyebrow). There’s anger alongside a cool recognition of “colour class bullshit” that pervades all aspects of Delroy’s life. Putting the spotlight on privilege couldn’t be more timely; Dyer and Williams are experts at it.

Photo by Normski Photography