If anywhere should host a state-of-the-nation play it’s surely our nation’s theatre. Roy Williams and Clint Dyer’s new work is an intelligent example of the genre. Full of insight and observation, their writing is expert. That said, it’s easy to imagine that the show will be primarily remembered for the extraordinary performance from its sole actor – Rafe Spall.

Williams and Dyer really have done a great job. The death in the title covers that of their character Michael’s father. The complex relationship between the two men, indeed the whole family, provides an intimate drama with plenty of humour. But the writers’ concerns are much wider, injecting the play with an urgent directness.

As well as getting to know a family, Death of England is a brilliantly observed look at a white working-class community and suggests a summation of the state of masculinity as much as race relations in the country. That’s a lot, and at times ‘issues’ feel forced, but Dyer’s direction of his text powers through.

Focusing on Michael’s father’s racism, Brexit and the Far Right raise their ugly heads. But Williams and Dyer want to point out that racism isn’t a fringe problem. That the father’s twisted logic includes a “time and place” for bigotry (criticising those who are too open about their prejudice) proves chilling. Michael knows he should have challenged his dad more and we can see the impact it has had on his friendships and his family. His cry to “search my history” may come in the context of the cache on a laptop but has far wider implications.

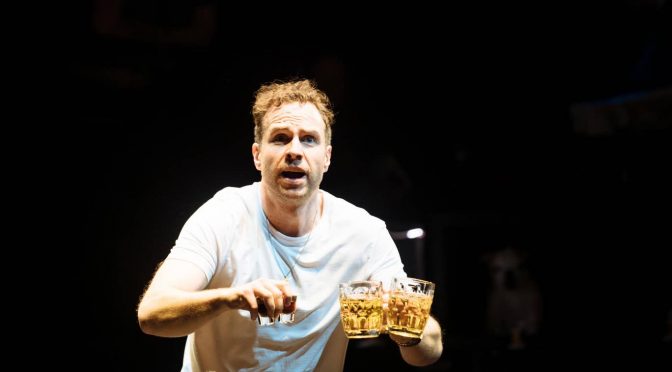

This root-and-branch examination of our country’s problems rests on Spall’s shoulder and he really is magnificent in this once-in-a-lifetime role. Addressing the audience throughout, and interacting with them a good deal, for all his faults, his patter and honesty make him appealing and often funny.

Spall’s is an incredibly physical performance, not least since a cross-shaped stage takes up a good portion of the theatre’s pit seating. With the character fuelled by drugs and alcohol, as well as rage, the switches from aggression to grief are frequent and sudden. The speech is nearly always at break-neck speed. Add the frequent shouts and tears (aside from worrying about Spall’s vocal chords) and it’s remarkable you can hear what he is saying so well.

When it comes to depicting other characters, Spall shows further intelligence. These are impersonations that Michael is making, the aim isn’t to bring another figure onto the stage but show Michael’s version of them. Getting to meet the whole family in this peculiar manner is wonderfully layered and brilliantly executed, serving Williams and Dyer’s play to perfection.

Until 8 March 2020

Photo by Helen Murray