What it’s all about is simple – Burt Bacharach’s wonderful music – somewhat grandly described as “reimagined”. The brainchild of performer and arranger Kyle Riabko, this mash-up of much-altered classic songs takes the idea of a tribute show to a whole other level. It’s a must for fans of good music.

It’s really only theatre in a loose sense – the songs are woven together musically, but there are no detectable themes or stories. Instead, there’s an atmosphere of conviviality and overall relaxation. The show is full of wit and surprises, which are probably more obvious the more you know about the music. And it’s beautifully dressed, with a boho-chic set by Christine Jones and Brett Banakis.

Be warned, though. As an indication of how fresh Riabko’s ear is, the loud guitars proved too much for a couple of visitors. If some of the versions push the songs too far, it is always with the best of intentions and the skill of the performers cannot be questioned – it’s a privilege to hear talent like this.

If you think of these songs as old friends, this is less about revisiting them, and more about learning something new from them. A stirring tribute to Bacharach’s genius, showing how strong the great man’s writing is, it’s no surprise that he’s supported the show. And what more of a recommendation could you want than that?

Until 5 September 2015

www.menierchocolatefactory.com

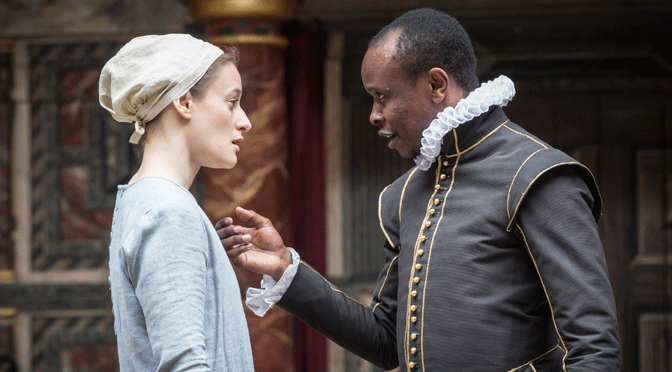

Photo by Nobby Clark