Into a no-name town, sometime when the West was wild, walks a wanted man. He’s doubly in demand because all the guys who used to live there have gone missing. The twist is that he’s transgender. Cue the show’s sell, that Cowbois is “a rollicking queer Western like nothing you’ve seen before”. They aren’t joking. Charlie Josephine’s show, which they co-direct with Sean Holmes, is tough to describe.

I guess, in a way, we have seen Westerns like this before – Josephine is playing with cliches. It’s a sensible genre to adopt if you want to explore masculine identity. The story itself is solid, the characters well written, and the twists great. Oh, and the show is a romance, with fantasy thrown in, powered by two superb central performances from Sophie Melville, as saloon owner Lillian, and Vinnie Heaven as the bandit on the run, Jack.

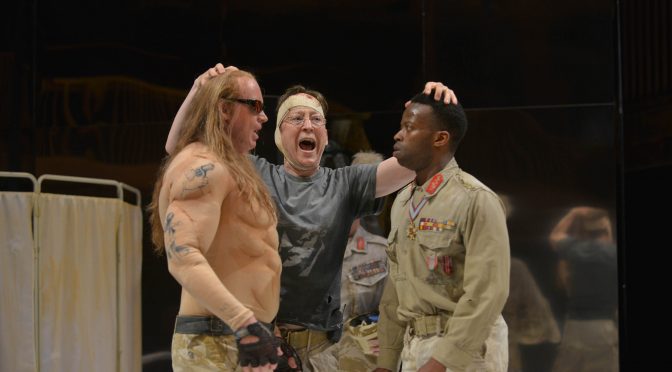

All the tropes make the show funny, and the cast play up to them brilliantly. Melville and Heaven have a great handle on the humour and are aided by energetic performances from, in particular, Emma Pallant and Lucy McCormick. Paul Hunter has a great turn as a drunk sheriff on another journey of self-discovery. It’s affirming and inclusive (of course), even jolly – but none of this goes far enough to pin down what’s going on.

The energy does dip. Maybe it’s a deliberate irony that when the men come home, the play sags; there’s tension but we care less about the new arrivals and the comedy takes a while to get back up to speed. There are too many stories to do justice to. Sensitive performances from Lee Braithwaite and Bridgette Amofah seem wasted – maybe that’s just an indication of how interesting all the characters are? But the show does get a little messy.

Music goes a long way to hold everything together – Jim Fortune’s work, and the onstage band, are superb. Heaven has a voice that is… well, they are aptly named. Indeed, Cowbois’ biggest failing is that we don’t get more songs. But what really solidifies the show is the excellent movement work, credited to Jennifer Jackson. Highlighting how performative gender is and adding touches of fantasy through choreography, the way everyone moves is worth paying attention to. A marked majority of the show is played to the audience – Josephine and Holmes highlight how aware of they are of us. The result is compelling. Maybe, magnetic is the word I’m searching for?

Cowbois gets crazy. Even before the finale, featuring a slapstick shootout (great fun), there are party scenes that mix violence and euphoria in a startling fashion. “If in doubt dance” might sum up the approach. And, by the way, a show-stopping cameo from LJ Parkinson, as a bounty hunter hoping to catch Jack, is jaw-dropping. Josephine has created a unique, uncanny world that pushes towards something new. Theatre often provides a space to invent and imagine – to play, in a way – but to take a show to this extreme is audacious. What’s the right word for Cowbois? I’ve got it. Fearless.

Until 10 February 2024

Photos by Henry T © RSC