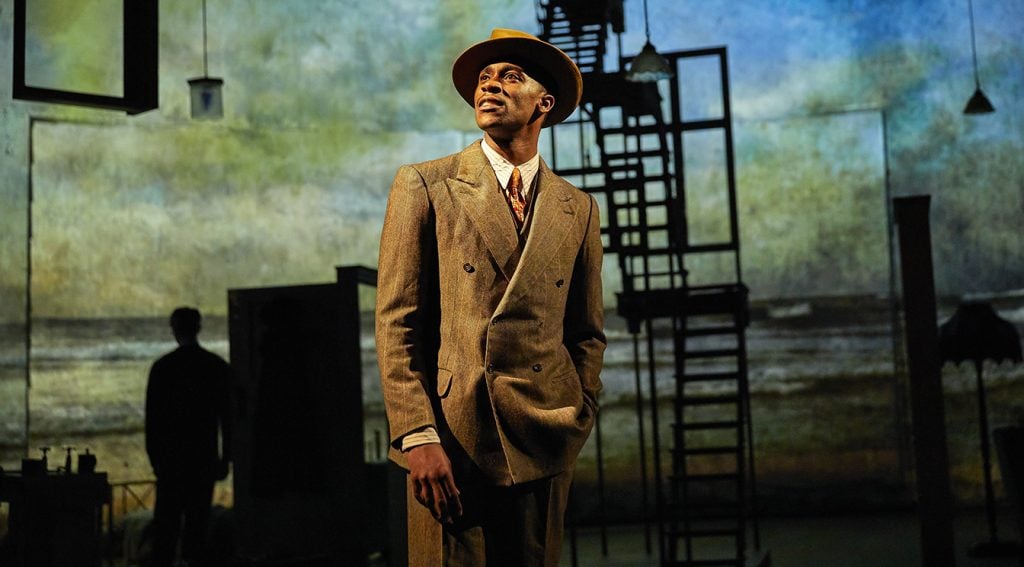

This week the National Theatre’s fund-raising offering is sheer class. Carrie Cracknell’s 2016 production of Terence Rattigan’s play is a traditional affair that oozes quality, with a solid script, stunning set and stellar performances.

The Deep Blue Sea is far from easy sailing. It starts with its heroine, Hester, having just attempted suicide, as the affair that broke her marriage is coming to an end. Concern over mental health has progressed since Rattigan was writing in 1952 but the playwright’s insight into depression offers much to learn from.

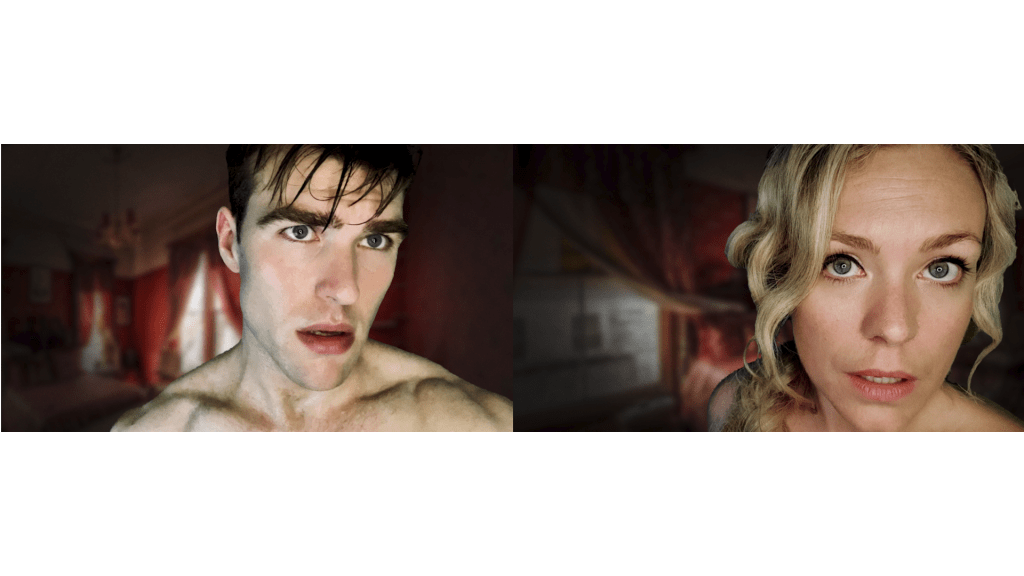

Rattigan’s preoccupation, however, is Hester’s passion. Her love for her husband, eclipsed by that for RAF pilot Freddie Paige, is fascinating. The romance is dangerous – this sea is stormy. Hester sees no chance of escaping a love that will not work: she and Freddie are “death to each other”. The production’s first triumph is to make sure Rattigan’s piece doesn’t descend into melodrama.

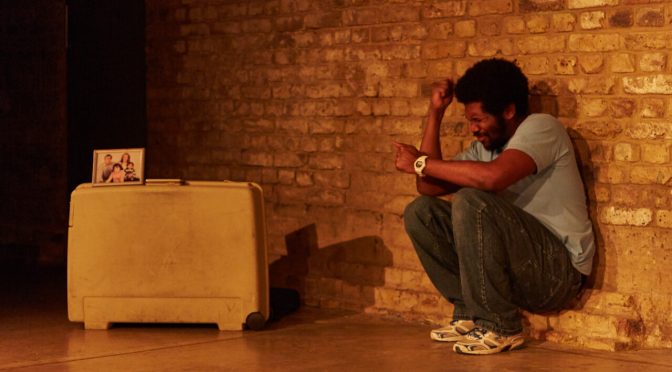

The love triangle provides strong roles for Peter Sullivan and Tom Burke, who are excellent. Their chemistry with their leading lady is astonishing. Burke is especially strong in making the occasionally odious Freddie convincingly alluring as an “homme fatale”. But the show belongs to Helen McCrory whose performance as Hester is flawless. Sharp and wry, the mix of “anger, hatred, shame” is conveyed in every move.

There’s a sense of British reserve behind all the action, darkly adding to the potency, but McCrory and Cracknell keep this as under control as Hester’s emotions. Moments when Hester is alone and can let go – holding her face to the light or crawling on the floor in desperation – are awe-inspiring in their emotional power.

Focusing on a sense of community within the boarding house setting, aided by Tom Schutt’s impressive set full of solicitous neighbours, means Cracknell adds to the play. A brilliant scene where Hester is joined by the women in the piece (played by Marion Bailey and Yolanda Kettle) alters our focus. It’s a move all the more remarkable given that the play, through Rattigan’s biography, is often discussed for its gay subtext.

If interested, try to track down a copy of Mike Poulton’s play Kenny Morgan, about the suicide of Rattigan’s lover (and a fascinating work in its own right). There is a danger that The Deep Blue Sea can be overpowered by this biographical note. But Cracknell has provided a space for the play to exist independently; an achievement for any revival that makes Rattigan’s script and his legacy stronger.

Until 16 July 2020

To support, visit nationaltheatre.org.uk

Photos by Richard Hubert Smith