As the winner of the prestigious Papatango New Writing Prize, Luke Owen gets his first play, Unscorched, staged at the Finborough Theatre. Packing in the critics last night, the scene is set to judge the script, and it’s easy to see why it won as it’s a strong piece. But just as impressive are the performances from two players: Ronan Raftery, who takes the lead role, and his love interest, played by Eleanor Wyld.

Back to the playwright. Owen’s unsavoury subject is child abuse, with the action based around an office where pornography is analysed in order to assist the police. We know it’s an unpalatable job; the first scene, with a brief but emotive performance from Richard Atwill, brilliantly shows a worker having a breakdown because of the traumatic material he is exposed to.

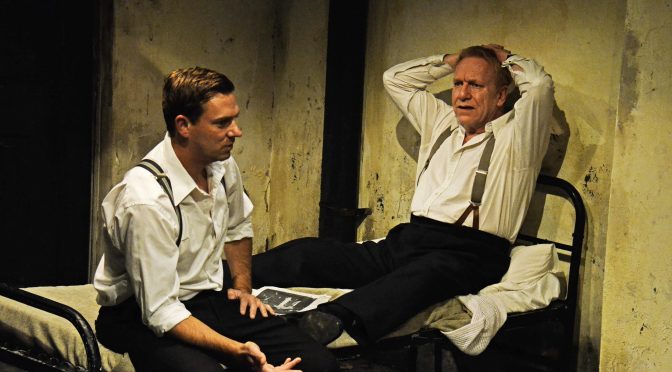

Enter our new recruit Tom (Raftery). With the bravest of intentions, the long-serving Nidge, performed capably by John Hodgkinson, mentors him. Seemingly immune to the horrors he watches, Nidge makes us aware of the toll this necessary work takes. And Tom is carefully watched by his boss, who has a “buddy” approach to management that strikes a jarringly comic tone. George Turvey convinces in this role, pointing out the therapeutic potential of an Xbox and promoting paintballing – as if these really could be solutions.

It is the romantic writing, about Tom and his new love affair, which is best and highlights Owen’s intelligent voice. As with the main subject matter, the relationship is written in an admirably understated fashion. Careful to avoid prurient touches, it feels authentic and shows the effects that working in such a horrible field have on ordinary people and this likeable couple in particular.

Satisfying as it is, the relationship Tom starts out on could have been even more of a focus to the play. A series of (too) brief scenes start to become a touch frustrating. Perhaps the direction from Justin Audibert could have been slightly tighter. The astoundingly efficient set from Georgia Lowe works hard but time is taken up preparing for very short scenarios so it feels as if the play needs a bigger stage. Although given the quality of the writing and performances, it surely deserves one.

Until 23 November 2013

Written 1 November 2013 for The London Magazine