Paul Grellong’s strong play works well as both a think piece and a thriller. Set in Harvard, a professor who invites a right-wing speaker to a prestigious symposium causes predictable trouble that escalates into tragedy. With the help of director Dominic Dromgoole, and a crack cast, this quality affair is a success.

First the debate, and top marks for topicality. Arguments for and against the invitation are set out well. Free speech versus the feelings of students is only one angle. Our professor, Charles Nichols, wants to defeat the Neo-Nazi believing that the answer to hate speech is more speech. But Nichols is a narcissist, full of pride and privilege, even if we don’t doubt he’s one of the good guys. Julian Ovenden is perfectly cast in the lead and does a great job. The arguments are clear, presented with a cool passion, while there are just enough hints that something else is going on.

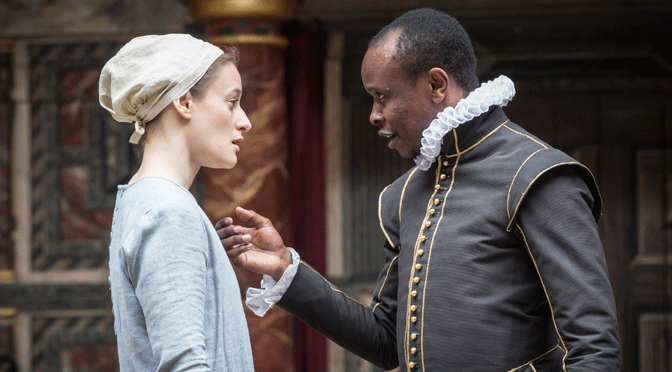

Students past and present argue with him, providing neat roles for Michael Benz, Katie Bernstein and Giles Terera. There is more to each than meets the eye. Meanwhile the Dean, played by Tanya Franks, isn’t happy either as her friend Nichols is turning into her biggest problem. Franks is perfect at showing underlying tension, making us wonder if her problems are personal or political. It turns out everyone here has other agendas.

As motives come to light, the play contains twists. OK, there aren’t any gasp out loud moments. And moving the action back and forth in time might be a bit clearer. But the sense of disappointment over some characters or a wish to cheer others on is real and shows how smart the writing is. Plus, all those extras complicate the debate in an intelligent way.

Campus dramas can be rarefied. The Power of Sail doesn’t quite escape that problem and, although Dromgoole keeps the pace quick, in general the characters are too naïve. How caught up everyone is in their own world might be explored, how their actions have wider consequences emphasised, instead everyone just seems a little out of touch. Nonetheless, what could be a dry subject, although important, is made dramatic and the production impresses.

Until 12 May 2024

www.menierchocolatefactory.com

Photos by Manuel Harlan