Sarah, Scott, and Simon are here to save the world. Or at least have a serious word with it. Travelling from Australia to present a speech, in the guise of a community meeting, this show is smart, important, and impressive.

The trio describe themselves as “intellectually disabled” – or neurodiverse – debate about the term is acknowledged. What they reveal about how they are treated by society begins by highlighting how difficult public speaking is for them. Here is the first move to get a lot of the audience onside.

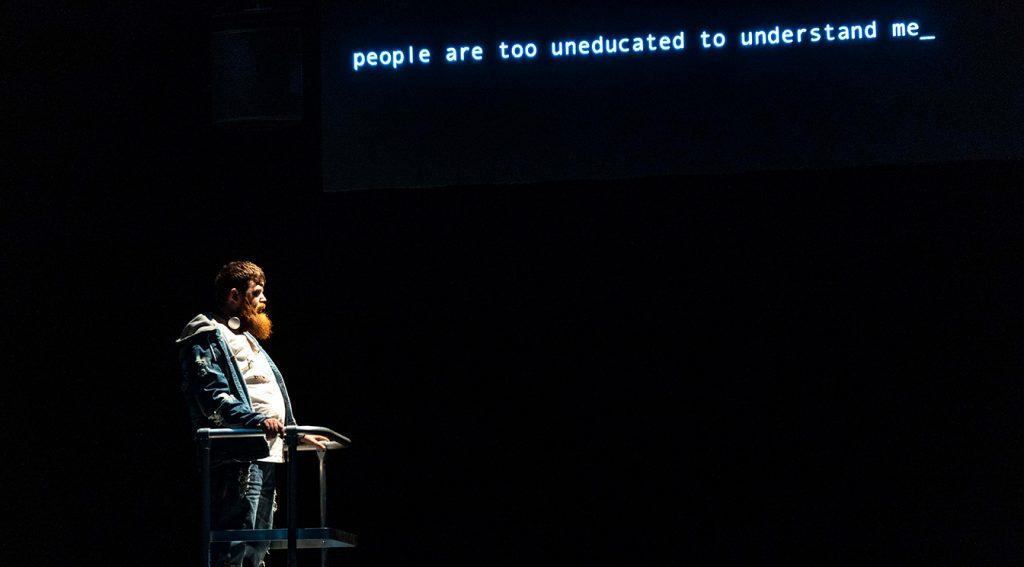

Surtitles are a sign that it might be difficult to understand what is being said (it’s not really that hard). But the captioning has comedy touches and becomes a character in the play. The show is funny and, for much of the time, wears its issues lightly. The humour is, again, a persuasive move.

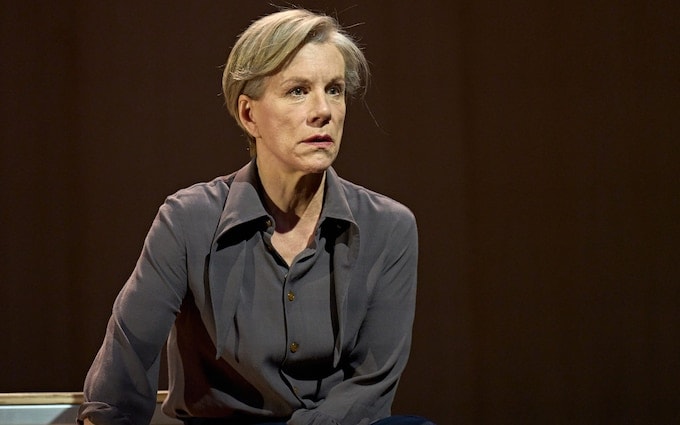

Comedy is joined by anger and honesty as we get to know the those on stage. A few jokes, some eye-opening history, and some frank admissions add appeal. The performers – Simon Laherty, Sarah Mainwaring and Scott Price – create a dynamic between their characters that intrigues and enforces individuality.

Plenty of topics are discussed – some too fleetingly. The show has a lot of authors: Mark Deans, Michael Chan, Bruce Gladwin, and Sonia Teuben as well as the cast members. Gladwin also directs and keeps the action focused. But the material here could easily be expanded and sometimes that is frustrating.

Back to that text, the team appreciates it is hard to draw your eye away from a screen. The audience is being aided by artificial intelligence. Here’s where the show is superb. Siri is sinister isn’t she (rather, it)? The technology is used to argue that, one day, everyone might share that disabled label. After all, our neurones all work differently to a computer.

Getting people interested in a cause by bringing it close to them is a neat move in an argument that also adds theatrical tension. I can’t imagine many disagreeing with what they hear – but the piece is enjoyably persuasive. And if theatre can save the world, it might very well be like this show.

Until 22 October 2022 and then on tour in Brighton (26-28 October) and Leeds (2-5 November)

Photos by Kira Kynd