Peter Gill’s short new play tackles big topics of old age and young love. It’s about the memories that remain with us and not all of them are happy ones. But magic comes despite – or maybe because of – the subject matter. This play is beautiful.

The two main characters, Colin and Alex, live together in a care home. Despite struggling when interacting with others they address the past with startling articulacy. Gill imagines minds that are active despite bodies struggling to communicate (listen out for another example). Examining “the state of memory” this is a depiction of old age that’s dignified. How rare is that? And it leads to strong performances from Ian Gelder and Christopher Godwin in the lead roles.

The family that visits Colin and Alex can’t see, or imagine, the real state of their loved ones’ minds. A son and a niece, further fine performances from Andrew Woodall and Claire Price, get on with their lives, unaware that Colin and Alex are doing just the same. The roles provide us with backstory brilliantly. The characters condescend; they see Colin and Alex holding hands as a “small mercy” given the care homes other residents. But the older men aren’t asking for sympathy and are their own harsh critics.

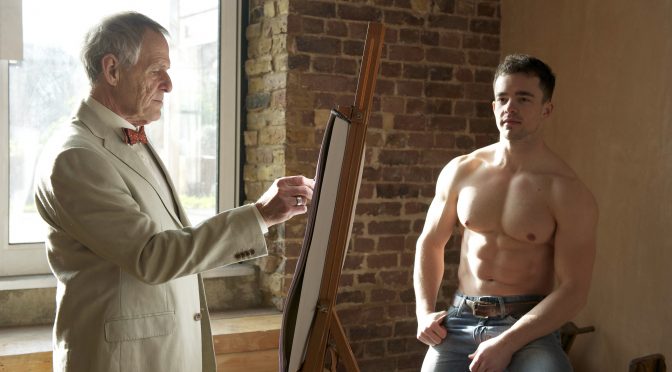

Two younger men join the stage as well. Figures from the past, but not, as you might expect, younger versions of the main characters. These are two past affairs, failed ones at that, brought vividly to life by Sam Thorpe-Spinks and James Schofield. The scenario gives insight into gay life from long ago but doesn’t blame prejudice for everything that happened. The interwoven comments and reflections are romantic but also recriminatory. The delivery is aided by the sure direction of Gill himself alongside the talented Alice Hamilton.

If none of this strikes you as happy stuff…fair enough. Where’s the beauty I mentioned? How about the clarity of thought on offer in a play with two men losing track of so much. Gill doesn’t entertain melancholy or indulgence. Instead, there is detail to transport you into other lives and take you back in time. The descriptions of London of the late 50s and early 60s, with student instigators and hippies, are marvellous.

The precision is incredible, you can see and hear the scenes recounted yet without being overwhelmed by minutiae. And all to build a love story. Not that from the men’s youth but in the here and now. It’s not the kind of romance we usually see (especially between men). But Gelder and Godwin make the affection and support between the Colin and Alex moving and Gill’s play is a beautiful thing.

Until 12 November 2022

Photos by Steve Gregson