A ‘free adaptation’ by Tennessee Williams of Chekhov might sound like a strange idea. The Russian playwright is, well, Russian, and his works are full of reserved Slav emotions and characters who repress themselves in a manner we don’t associate with Williams. Yet Chekhov’s writing about the ‘interior life’, which made his theatre revolutionary, engaged the American writer. The Finborough Theatre gives us the chance to see his exploration in The Notebook of Trigorin, his version of The Seagull.

You might want to brush up on the original version – it makes for an interesting game of compare and contrast – but it is by no means essential and you’ll probably be enjoying this production too much to bother. Williams tightens what is already a compelling plot, and director Phil Willmott gives the action a lively pace.

The play is set in the family home of Arkadina, the most famous actress in Russia, during her infrequent visits to see her son Constantine who is looked after by her elderly brother Sorin. Accompanied by her younger lover, the writer Trigorin, she walks in on several sets of unrequited love. Constantine is loved by Masha but adores their neighbour Nina. Masha is followed around by Medvedenko but wants nothing to do with him. Her mother Polina is obsessed by the local doctor Dorn. Arkadina’s arrival doesn’t make the situation simpler – Nina falls in love with Trigorin. In an unnecessary addition from Williams, Trigorin falls for a stable boy who goes swimming a lot. Thankfully, for brevity’s sake, he stays in the lake.

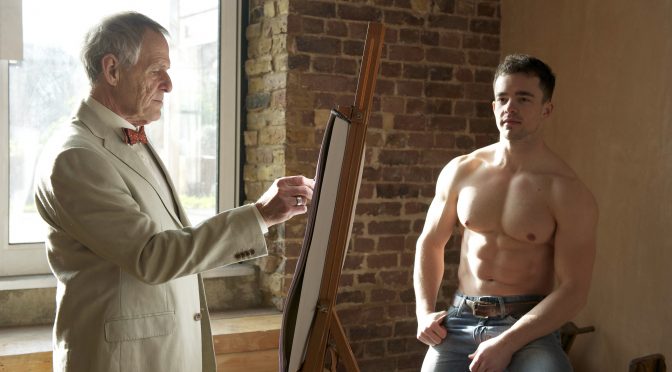

As these situations play themselves out, the characters deal with their dreams and ambitions. Constantine, played with brooding adolescent intensity by Rob Heaps, wants to be a writer. Nina (Samara MacLaren) hopes to become an actress and develops from a shy girl into an impassioned woman. Andrea Hall is wonderful as Masha, who struggles to abandon her unrequited love and marry Medvedenko, played with great charm by Daniel Norford. In a beautifully pitched performance, Lachele Carl’s Polina rails against Morgan James’s Dorn. His Doctor is one to strike from the register, a louche seducer played with great sexual presence whose treatment of Richard Franklin’s movingly vulnerable Sorin is deeply cruel.

Williams’ adaptation of the play is most noticeable with Trigorin. Stephen Billington reads his notebooks as a voiceover. This may have a strange Chandleresque quality but allows a distance between his interior voice and a wonderful performance on stage where we are never quite sure how genuine this man is. Trigorin fits that particularly American role of the flawed narrator. He is an artist first and foremost; keen to scribble down a potential story, to exploit a situation for narrative and quick to judge others.

What Trigorin and Williams share is their interest in Arkadina. Always a great role for an actress, in this version, she is combined with Williams’ other indubitable heroines. Women in genteel poverty are a common trait in his work, as are those who live their lives performing a role. Carolyn Backhouse takes on all this with great aplomb. She performs with humour and power as a woman with a fragile grip on what is precious to her and a ferocious ability to defend it. She is like Blanche DuBois on steroids, more condemned than she might deserve to be. In the final scene, Willmott exploits this tension especially well, leading towards a dramatic tableau that reaffirms the plays concerns with the necessity and danger of artificiality. The whole of this superb cast are used. Their combined efforts more than make this production worth seeing and the play itself offers fascinating insights into both Chekhov and Williams.

Until 24 April 2010

www.finboroughtheatre.co.uk

Photo by Scott Rylander

Written 1 April 2010 for The London Magazine