An African American man volunteering to be the slave of his white friend is the core idea that guarantees Suzan-Lori Parks’ play is memorable. Is it brilliantly provocative, instantly horrifying or a gimmick? That Parks acknowledges all possibilities is to her credit.

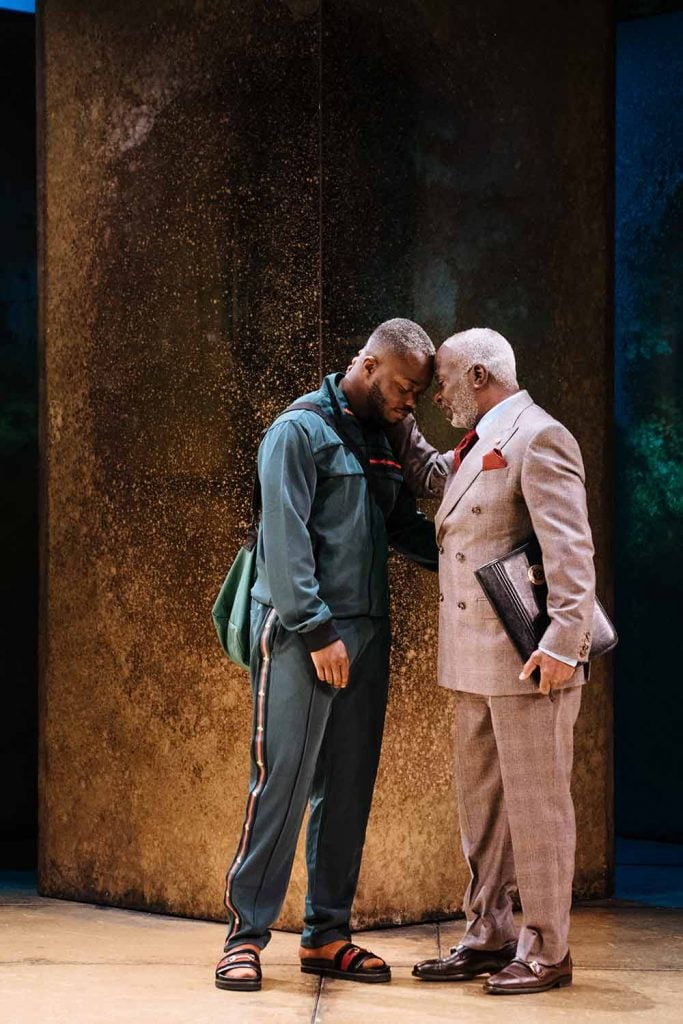

Coming after a police assault, Leo says he will be safer as the wealthy Ralph’s property. Commentary doesn’t come more damning. Parks uses the experiment to raise the issue of inherited trauma and invites scepticism – Leo’s an artist and there’s the chance his project is a performance.

The ramifications, set over 40 days, prove dizzying even if they are well handled. Even the harshest critic couldn’t say White Noise has just the one trick. In exploring the ‘virus’ of racism Parks thinks big and commands respect.

There is an intelligent contribution on the topic of ‘woke’ culture. As the men’s partners, Dawn and Misha – a YouTuber and a lawyer respectively – try to make the world a better place, and Parks documents their trials and hypocrisies with a steely eye and a keen ear (the verbose dialogue is something else).

The idea of privilege is examined, too – forcing all the characters to ‘check’ themselves. This high-achieving quartet of college graduates seems to have no money worries. Instead, there is a cloying concern for status. And there’s the superb conceit of a – literal – ‘White Club’ that Ralph ends up joining. A conspiracy I found particularly creepy.

The play fizzes with ideas – but not the stage. Of course, the experiment ends badly – that’s no surprise – but the effects on all disappoints. Despite the efforts of a strong cast – Ken Nwosu, Helena Wilson, Faith Omole and James Corrigan – the friends fall apart too quickly and feel like puppets for Parks.

The confused relationships and affairs between the four prove tiresome and predictable. A desire to be comprehensive and even-handed results in four excellent monologues (Nwosu’s comes first and is especially strong), but these make the show very long indeed. Each character spends too much time thinking about themselves to be appealing. With all the self-awareness, much of dialogue sounds like a mission statement.

Director Polly Findlay respects Parks’ considered arguments and adopts a slow, even pace that compounds the problem. The scope and insight of Parks’ writing is impressive, but more focus might make a better play.

Until 13 November 2021

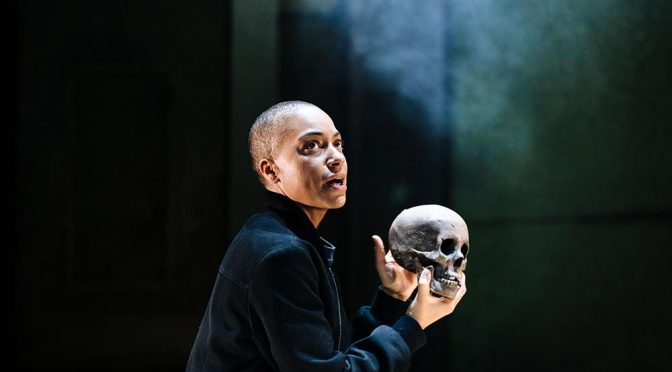

Photos by Johan Persson