Start your play with a Jewish family in turn of the century Vienna and an audience is sure to have expectations. Tom Stoppard knows this, of course, there’s little Tom Stoppard doesn’t know. But the craft behind his new history play is a marvel. And the emotional power of Leopoldstadt every bit as strong as you’d imagine.

Starting in 1899, things are convivial and a little confusing. We’re introduced to Hermann Merz and an extended family that – like the cast – is huge. As we see them grow up, and the family grow, it’s tough to keep track. Thankfully, Aidan Mcardle and Faye Castelow take the lead as Mr and Mrs Merz, with marital troubles and his conversion to Christianity, to focus on.

The discussions are fascinating and highbrow – after all, this is Vienna and they are Jewish! Identity, mostly, but all manner of politics and culture. There’s a sense of excitement and pride about the city that roots the play. Stoppard sets out issues clearly – it’s a great lesson in intellectual history – but also makes debates feel alive as the characters live them.

Admiration for the cast grows as their characters age. Mcardle and Castelow triumph as Stoppard takes us to the end of their characters’ lives. Jenna Augen’s Rosa, an American relation, is also a highlight with a performance that goes from strength to strength. And it is a thrill to see relatively small roles so fully developed. Sam Hoare is just one example as a British journalist who marries into the family. Director Patrick Marber has neglected nothing, like Brigitte Reiffenstuel’s exquisite costumes, the attention to detail is winning. A sense of grandeur and respect appropriate to the subject infuses the show.

If there are slower moments, the dramatic point behind the depth and detail brought to Leopoldstadt becomes clear as history progresses. A family encounter with Nazi’s is difficult to watch. Seeing the characters, we have so deftly been made to respect and admire, cowered and humiliated is painful. What happens feels unbelievable. Shocking. And that’s quite an achievement when we all know the awful history.

Stoppard gives us the space to think about history. A scene set in 1955 focuses on the encounter between a younger generation: Leo, who escaped to Britain, and Nathon, who has survived a concentration camp. If Sebastian Armesto and Arty Frouhsan play the roles broadly, they match the peculiar underlying tension to the scene which compliments the extremes of their experience. As Leo learns the fates of his family from Augen (who makes Rosa’s suffering palpable) we are made aware of how close we’ve become to them all leading to a conclusion of intense theatrical power.

Until 30 October 2021

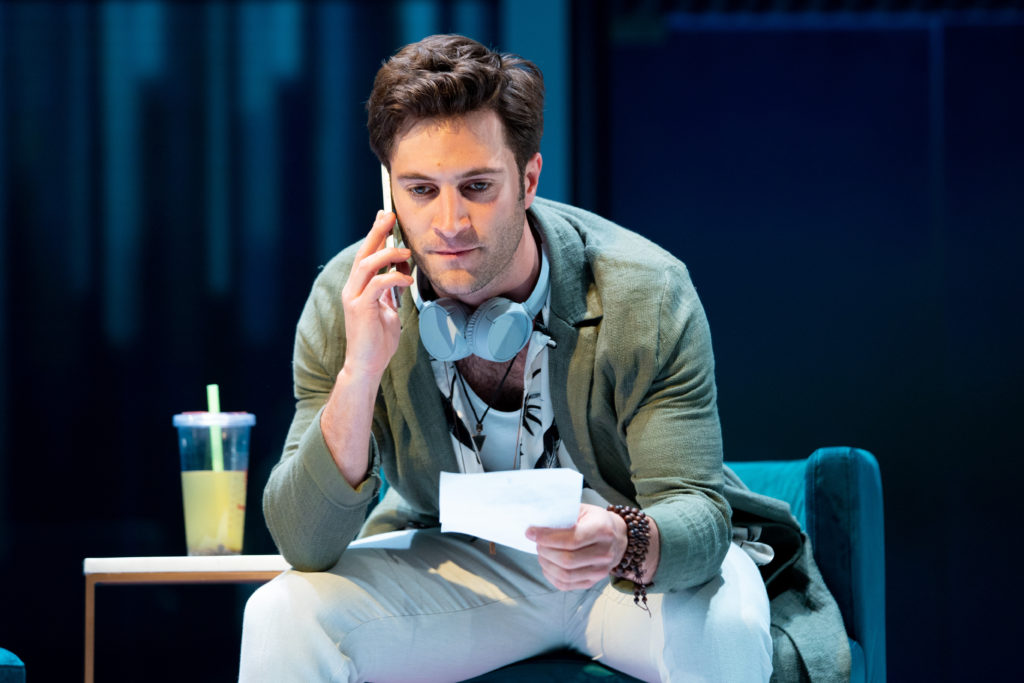

Photos by Marc Brenner